Amelia Groom

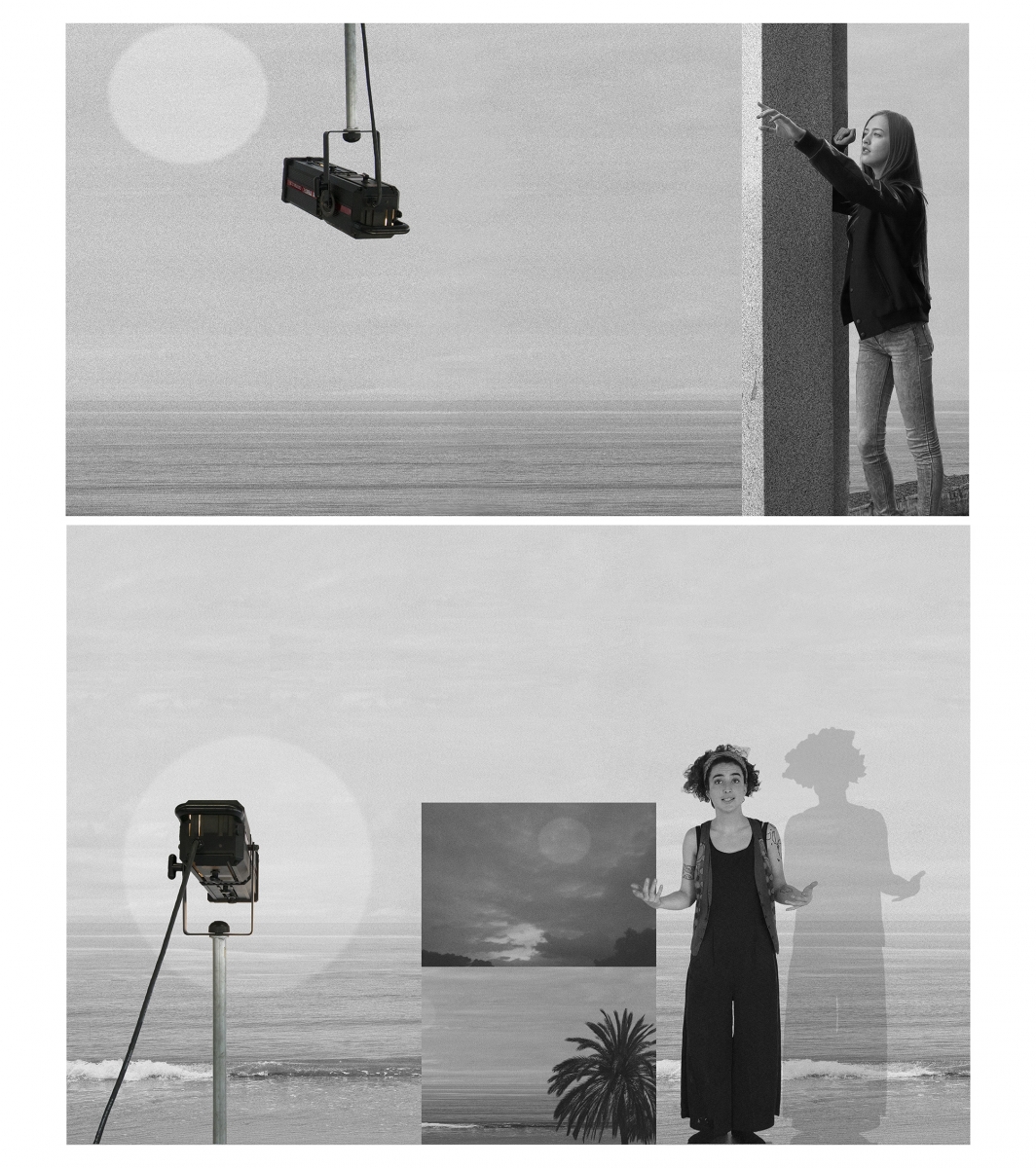

For his One Year Performance 1980-1981: Time Clock Piece (fig.1), the Taiwanese artist Tehching Hsieh set out to register his arrival at a worker’s time punch clock in his Manhattan studio, every hour, on the hour, day and night, from April 11, 1980 to April 11, 1981. He photographed himself each time he ‘clocked in’, and the thousands of resulting images were then made into a time-lapse film, condensing 365 days into six minutes.

Figure 1. Tehching Hsieh, One Year Performance 1980-1981: Time Clock Piece, 1980-81.

At the foreground of the work’s multiple temporal registers are these two standard units of time: the hour and the year. But while the imposed mechanical structure of clock-time is perversely obeyed across an entire annual cycle, other standardised temporal measures are completely disregarded. Diurnal rhythms of light and dark (which are perhaps our most primal marker of time’s passage), as well as the body’s circadian rhythms of healthy sleep patterns, are bypassed – and other standard units that are longer than an hour but shorter than a year (weeks, months, seasons) do not register at all.

Certain temporal measures are embraced as the work’s primary material, while others are overridden, so that Tehching’s performance is one of being always right on time while also becoming totally out of synch with the rest of the world. And while the clock moves steadily and predictably, with its homogeneous and interchangeably abstract units, the body that tries to obey it registers other temporalities. The 133 punches that Tehching failed to make, out of the 8760 hours that are in a year, are a crucial component of the work, because they are the corporeal slippages, were the full internalisation of clock-time is shown to be impossible.

In the time-lapse film, which is assembled from the 8627 photographs (one for each clocked-in hour), we encounter organic cell renewal as a different sort of time-keeping device, with Tehching’s hair left to grow out from shaved to shoulder-length over the 365 days. We also see the enfleshed temporalities of endurance and exhaustion, with the accumulated effects of physical decline as he becomes more and more pallid and bleary-eyed over the thousands of hours. With each day passing as less than one second, the film shows the clock device firmly in place on the left side of the image, whirling menacingly, as the body on the right continually flitters and fluctuates. His growing hair and the ripples of his shirt take on an unruly a life of their own in the moving image, while his gaze maintains a striking steadiness, piercing through all the surrounding motion.

Time-lapse is a form of moving image that speeds time up by leaving most of it out. The word ‘lapse’ relates to slipping, sliding and falling —as in collapse (falling down), relapse (sliding back) or elapse (slipping away). And this is what time tends to do; it slips away from us. But the time lapse film is both a shedding of temporal bulk and a retrieving of the continuum, in distilled form. It’s a filtering out of real time which then traces otherwise undetected movements —like the gradual growth of Tehching’s hair that is only made visible to us as movement in this reconstituted six-minute long year.

So this One Year Performance deals with clock-time, hair time, the time of the image, of the documentary trace —as well as cinematic time, where a string of stills is animated through rapid succession. And through all this is another sort of temporality that the performance deals with, which is the time of work. As we know, the notion of waged labour depends absolutely on a model of time as something broken up into equidistant units, and made universally measurable. In order for it to serve and perpetuate capital’s principals of compartmentalisation, exchangeability and expansion, time in early modern Europe needed to become homogenised and quantitative. This is a process that has been examined at great length by many historians and theorists; the mechanical clock and the standardised twenty-four-hour day establish crucial preconditions for capitalist regulation, production, exchange, accumulation and debt.

As the mechanical clock makes its temporal units abstract and interchangeable —regardless of real experience, or site-specificity, or particular embodiments— it is closely related to that other great abstraction, money: one minute is supposed to be the same as any other minute, just as one pound is the same as any other pound. And with bodies reduced to their labour power, they also come to be treated as interchangeable units –the number inscribed across the front of Tehching’s worker uniform in the Time Clock performance evokes this manoeuvre, where flesh is reduced to an interchangeable component of productive machinery.

Figure 2. Checking-in late in, 9 to 5, 1980.

I want to now zoom out for a moment, and think about a little coincidence. It just so happens that in late 1980, as Tehching was punching away at his time-clock, Dolly Parton’s hit track 9 to 5 was saturating the airwaves, topping the pop and country music charts for many consecutive weeks. The song appeared on Parton’s 9 to 5 and Odd Jobs, a concept album about working which features Parton on the cover draped in a cumbersome assemblage of signifiers, including a typewriter, a paint roller, a lawnmower, a briefcase, architectural blue prints —and of course stilettos and a bright smile. She stands for the perfect multi-tasker female worker: over-skilled and under-paid, occupied but always available, anonymised and uncredited but still smiling.

The song was written for the film 9 to 5, which was released at the same time —and it plays over the film’s opening credits, where we see a montage of different alarm clocks going off, followed by shots of different anxious female workers rushing to make it in time to the office (where, the film goes on to show, they will be paid less than their male colleagues, who routinely steal their ideas and sexually harass them).

The film stars Parton alongside Jane Fonda and Lily Tomlin, as three fed-up secretaries who manage to kidnap their “sexist, egotistical, lying, hypocritical bigot” boss and run the office on their own. An enforced absence of unions is implied early on in the film, but the women manage to implement some improvements to their working conditions, introducing childcare facilities at the work place, as well as new part-time work options and greater flexibility with work hours. We learn that much of their struggle is temporal; it is about access to and regulation of time. One of the first things they do when the boss is gone, is remove the office time clock (which happens to look almost identical to the one in Tehching’s contemporaneous One Year Performance), so that workers are no longer forced to clock-in and clock-out.

Sadly, in 9 to 5, the struggle basically stops there, and the story falls short of any real structural critique. It ultimately affirms the capitalist ideals of ever-increasing productivity and concentration of profit: because as corporations like Google now know well, more flexibility and fun in the office equals enhanced worker efficiency. So rather than abolishing capitalist exploitation, 9 to 5 shows how good it is at adapting, as it feminises itself with a friendlier face.

There is nothing subversive in removing the disciplinary mechanism of the time-clock from the workplace, if its basic principles of discipline and servitude are simply reconstituted in new forms. And this is where the contemporaneous ordeal of Tehching’s One Year Performance: Time Clock Piece becomes a strikingly relevant visualisation of a historical process. For an increasing number of workers, the 9 to 5 working day has transformed into an all the time condition. As many have observed in recent years, capital’s growing dependence on immaterial and informational labour means that the time and place of work are no longer clearly delineated. More and more, work happens not in a ‘workplace’ but pretty much everywhere else. When we no longer have to clock-in and clock-out, we find that we are never really not working, and work becomes indistinguishable from life.

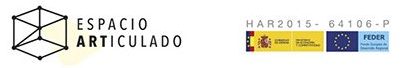

Figure 3 and 4. Art Time, Life Time, Tate Modern, London 2017. Images courtesy of Indre Neiberkaite and Tate Galleries.

As with earlier organisations of labour, this shift depends on specific equipment: because my ‘desktop’ can be carried around with me, it usually is. We once thought that the near-instantaneity of emails would free up more time for us, but somehow emails now seem to eat away at huge chunks of my days, and nibble into my nights. Our glowing screens are just one recent development in capitalism’s long-running erosion day/night distinctions —another new component of this process is the ‘sleep app’ that we are now invited to install on our phones, which is really a means by which our disengaged slumber can be turned into data production for corporations, so that even when we’re asleep in the dark we’re at work and under scrutiny.

Unlike the white, middle-class, American women in 9 to 5, Tehching in 1980 was an undocumented immigrant, who didn’t have the option to participate in the official waged labour market. Arriving in the US in 1974 by jumping ship from an oil tanker he had boarded in Taiwan, Tehching was illegal for the first fourteen years. As part of the undocumented immigrant labour force that America’s economy has long been completely dependent on, he made a living by cleaning floors and washing dishes for cash in downtown New York restaurants —usually during ‘after-work’ hours, while others slept.

If his Time Clock Piece historically anticipates current post-Fordist conditions of 247 legibility and availability, those conditions are not presented in the work as a totalising inevitability. Because according to the artist, his elaborate, arduous enactment of the meaninglessness of constant arrival opens up into something he calls ‘wasted time,’ where ‘free thinking’ (importantly: not ‘freedom’) becomes possible. Current historical conditions seem to make wasted or non-instrumentalised time increasingly difficult. With our dreams and desires mined as data —and all movements algorithmically measured, quantified and predicted— life is becoming so regulated that the question of how to really waste time is now a very real one. But within the excessive punctuality and clock-time obedience enacted in Tehching’s performance, there are also times, time that might be less immediately legible —times of elusion and refusal.

* This was a short presentation delivered as part of the event Art Time, Life Time with Tehching Hsieh and Lois Keidan at the Tate Modern in London on December 2, 2017 (fig. 3 and 4).