Paz Tornero

Notes on the hybrid,

the connected and the complex

The philosopher and art critic Brian Holmes defines as “extradisciplinary” the synergies between disciplines, which produce rigorous research in opposing fields away from art such as finance, biotechnology, microbiology, geography, psychiatry, etc. Thanks to them, what Holmes describes as “the ‘free play of the faculties’ and the intersubjective experimentation that characterize modern and contemporary art are promoted, as well as identifying” the spectacular or instrumental uses that are so often made of the aesthetic game’s surprising and subversive liberties” (2008, p. 206):

A new tropism and a new kind of reflexivity is put into operation here, involving artists as well as theoreticians and activists in a transition beyond the limits traditionally assigned to their activity, with the express intention of facing the development of a complex society. The term “tropism” expresses the desire or need to turn to something else, to an external field or discipline; while the notion of reflexivity now indicates a critical return to the point of departure, an attempt to transform the initial discipline, end its isolation, open new possibilities for expression, analysis, cooperation and commitment. This movement back and forth, or rather this transforming spiral, is the operative principle of what I will call extradisciplinary investigations. (p 205)

These actions generally thrive in spaces previously investigated in several articles published in this journal called “Spatial Politics,” according to Rosalyn Deutsche’s definition (1996). We remember from this description the preferred scenarios, manifestations of the city, the territory, the map, the place, the landscape, nature and the body. Likewise, it is important to take into account in this definition the concept of “space” in virtuality as a global / glocal connected place that immediately activates the creation, discussion and dissemination of art. A place also in outer space, outside air space, not subject to the sovereignty of a single State.

In the virtual space of globalization not only are we all connected, but our ideas, feelings, opinions, even our identities constantly navigate in a medium that unites the artificial with the natural. Fredric Jameson states that globalization and postmodernity are the same thing: “Globalization encompasses it in terms of information, in commercial and economic terms. And postmodernity, on the other hand, consists of the cultural manifestation of this situation” (Romero et al., 2004, p. 1). Roland Robertson (2000) states that globalization has to do with the way in which the understanding of the world is structured and that, thanks to international negotiations and technological innovations, space-time was standardized, which, inevitably, was at the same universal and individual time: “In other words, homogeneity went hand in hand with heterogeneity: one made the other possible. It was in this period when ‘the world’ was blocked in a particular way, like a strong change towards oneness” (p. 16). Homogenization and heterogenization (two seemingly opposite tendencies) complement each other and interpenetrate concrete situations. Manuel Castells (2014) states that we live in a social structure made up of global networks where a new culture appears, that of autonomy: “In order to fully understand the effects of the Internet on society we have to remember that technology is a material culture” (p. 11) According to Castells, there is no rupture of the community, or of interaction in a specific place but a reinterpretation of our relationships, of cultural and personal ties that could be part of community life about individual values and projects. Therefore, the process of individualization is not exclusive of a cultural evolution. It is the result of new ways of organising our activities in the information age, which give rise to the transformation of space, work life, economic activity, culture and communication:

But individualization does not mean isolation or, of course, the end of the community. Sociability is reconstructed in the form of individualism and a networked community through the search for like-minded people, in a process that combines virtual interaction (online) with real interaction (offline), cyberspace with physical and local space. (p. 13)

We move quickly. As in the past, the evolution of the mind is always associated with the joint evolution of the body. For this reason, for the artist and theorist Roy Ascott (2000), the great challenge of science and art in this new century is to find the nature of consciousness. Castells states that a subject in social sciences is necessary to help improve our understanding of the world in which we live and he proposes “Internet studies” (2014, p. 29). Ascott (2000), however, states that it is essential to establish a techno-ethic aesthetic that, in consortium with this new medium, allows artists to address the fundamental issues of our time such as “What does it mean to be human in the postbiological culture?,” “How is the ontology of the mind and body in cyberspace shaped?” and “How do we redefine nature and life in this scenario?” To begin to answer these questions, the author argues that it is the artist’s task to navigate the fields of consciousness that the new materials will generate and thereby obtain conclusions in accordance with the technologies inserted in our daily lives:

Artists, free from orthodoxy (although, like scientists, concerned about authenticity), are syncretic in their form of creation. They are willing to study any discipline, scientific or spiritual, any vision of the world —esoteric or mysterious— any culture, immediate or distant in space or time in order to find ideas or processes that can generate creativity. (Ascott, 2005)

It is in this scenario where space is established as a technoglobal cartography given that, according to the sociologist Roland Robertson (2000), although the territory has been constituted as a product of the economy, of the political and of the cultural, there is currently another important element to consider: space is crossed by science and technology and its activities respond to the totalitarianisms of information and finance: “Globalization is affected by the intersection of presence with absence, the interweaving with the ‘local contextualities’ of social events and of ‘distant’ social relations” (p. 3). For Jameson, the great modern works, particularly literature and then painting, pose the question of time and memory in a prodigious way; why at a certain moment the sense of time, of the past, was weakened. (Romero et al., 2004, p. 4) Remedios Zafra (2011) states that:

However, the value of these companies in each case, is not so much the device itself, but to conceive them as “spaces” which manage to gather millions of “I’s,” spaces that become part of affective relationships and that transform users into producers and content. Undoubtedly, these relationship structures also tell us about ways of distributing people and spaces not exempt from political significance. (p. 121)

The author, who ponders widely on the meaning of “identity” in the Web, affirms that the corporeal, the body, the one that coexists with digital connections, is not completely ours: “No matter how much you care for them, feed, apply make-up, implement, caress, kiss, make porn and everything else, bodies are ours, but not entirely ours. And there, the story becomes political” (Zafra, 2008, p. 138). The symbolic construction in the connected world supposes, paraphrasing Zafra, to question what we are, not as something given, but as something individual and modified socioculturally and susceptible to being altered in the material and biotechnological, but also regarding its meaning and its sociocultural value (2008, p. 138). Material bodies are not physically transferred to the Net, but their images are: “So that in the ‘images of the body’ and their cultural symbolization the socio-cultural identity assignments continue to perpetuate” (2011, p. 125). That is why it certifies that art is a territory of representation and so is the Internet. Both are scenarios of the factitious for representation and artificiality, where the contradictions and instabilities that arise when we rebel against our stereotyped identity can be visualized and coexist (2011, p. 125).

In this sense, the critic Mark Fisher defends the artist’s chimerical activity in the current post-Fordism, since our own desire is hidden from ourselves. To paraphrase the author, we do not know what we want mainly because the most powerful forms long for the unknown, the strange. Absences, which for Fisher can only be remedied by trained artists and communicators, allow us to visualize something other than what already (falsely) satisfies the majorities (Fisher, 2017, p. 115). Fisher, mentions with special interest the documentary maker Adam Curtis who knows the media in detail and attacks the Internet because: “It encourages the formation of solipsistic communities, interpassive networks of ‘minds as one’ and what they do is confirm rather than challenge the prejudices and presuppositions of each individual” (p. 114). Fisher adds that the Internet also encourages discursive platforms such as blogs that do not exist outside of cyberspace:

As the old media communication system is absorbed by the logic of public relations, as consumer commentary on a product replaces critical testing, certain areas of cyberspace offer a place of “critical understanding” that cannot occur elsewhere. Even so, it cannot be denied that the simulation of participation marked by the interpassiveness of postmodern media in general has produced a lot of respectful, parasitic and conformist content. (p. 114)

In the search for the meaning of the individual in this century, cyberspace is altering temporality in an unprecedented way. All the experiences that emerge outside of digital technologies begin to seem “anachronic experiences” for the new generations. Think of moral values and how they have changed radically in these last two decades, in the conversation by phone or on the street, in body contact and the clean looks of a screen between them. This temporality covers a plural dimension, since memories and real time are unified in a single conducting thread with the user being an intermediary between both temporary spaces. Paraphrasing the writer and philosopher Andrés Alfredo Castrillón (2011), chronological time, understanding everyday life and the affective life of the individual, is confronted by memory, by the story told in our memories. Therefore, the chronological order of the discourse disappears (p. 61), and that of remembered history. From this statement we should ask ourselves where, in this history, the individual is to be found as a virtual entity.

Physical and virtual spaces coexist along with memory, memories, multiple identities and alter egos between (e-)anachronic temporalities; a pluridimensionality of time as (e-)non-linear anachronism within the technodaily task.

Anachronic temporality in the virtual act:

the violation of time

The legacy of contemporary art of the last fifty years has led us to the current situation characterized by transgressive artistic action and its great performances of resistance. Among its many technological, ethical and aesthetic challenges that must be taken into account, Ascott affirms that it is necessary to balance the possibilities of new relationships on the Net and those offered by genetic, molecular and nanotechnological engineering: “Omnipresent and ubiquitous, the flood of human and artificial intelligence is unstoppable. At the same time, we are coming to recognize that the totality of the natural world is, in a sense, conscious.” (Ascott, 2000)

In relation to this plural, technological and dialogical temporality that develops from supposedly contrary spaces, the physical and the virtual, —and here we must remember again Castells (2014): “But it is not a virtual society. There is a close connection between virtual networks and live networks. It’s a hybrid world, a real world. It is not a virtual world or a separate world.” (p. 17)—, the art of the last decades has produced numerous examples to examine. Among them, it is worth mentioning in this article the interesting work of the Italians Eva and Franco Mattes, pioneers of Net Art, viral art, virtual “happening” and work on the Net since 2000. Their raw material is extracted from web technologies, public space, big brands, politics and propaganda. In short, a guerrilla art of information technologies and popular new electronic cultures. The masterful No Fun intervention of 2010 is worth mentioning, for the dialogical and temporal complexity that this piece contains.

The Mattes staged Franco’s suicide for the users of the Chatroulette video chat site. In this service, Internet users meet casually and can converse by video until any of the participants decides to leave the chat and move to another random pairing. A priori, this structure of interaction seems like just another virtual application that can seduce us to be used and thus provide certain leisure moments (or pseudo-conversions and pseudo-relationships) on the Internet. However, it has become mainly a showcase of exhibitionism with a high sexual content. Many participants use Chatroulette for a sexting relationship on camera, (which has unfortunately resulted in numerous extortions or sextortion), with a special increase in groomers (sexual harassers) and fraudulent advertising. (Bermejo, 2017)

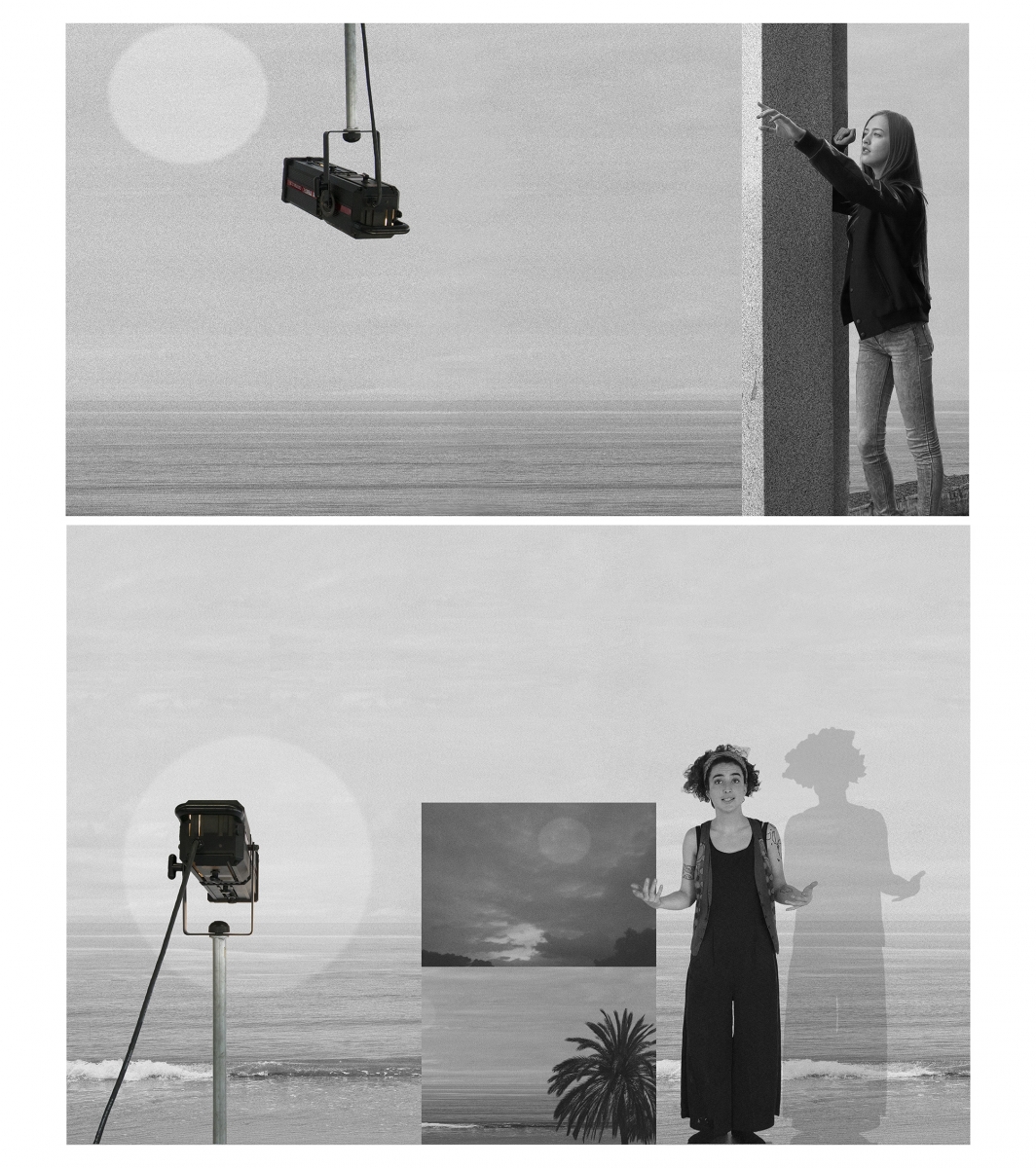

Under this atmosphere comes the work No Fun (Fig. 1). Franco Mattes appears hanging by the neck next to a large bright window to the right of the screen, allowing all the details of the scene to be clearly seen. The room where Franco’s supposed corpse is suspended is a mess. Numerous papers and other objects are scattered on the floor. A (premeditated) disorder that inevitably, forces us to make a deep reading to interpret what we see on the other side of cyberspace: “Of course nowadays, in its facets of fiction and nonfiction, these forms of ‘unfolding’ that want to safeguard the body still coexist with postmodern hypermobility. And they do it in a compatible game of tensions for globalized life. In fact, it is revealing that ‘being at home, being outside’ is today one of the epochal correlates of this hypermobility” (Zafra, 2011, p. 124).

If we look at the numerous elements perfectly designed in the frame, we find that in the lower right corner there is a fragment of the screen of a laptop (Franco Mattes) where the screen corresponding to the user’s (or users) face is subtly distinguished, which randomly in real time we find in this application. Due to this fact, if we study the composition carefully, we must rule out that we are looking at a photographic montage (hence many users question its veracity at first glance), which would result in an anachronic temporality in the construction of the image used, obsolete for this application since its main communication channel is the real time video generated by the webcam.

Figure 1. Fragment of the video online performance No Fun (2010), Eva and Franco Mattes. Accesible at Vimeo: https://vimeo.com/11467722

The work is available today in video showing both screens (Franco and the rest of the participants) on the Vimeo platform of the artists’ page. There is a series of excerpts from the performances of Internet users in Chatroulette who react to the alleged suicide. Some people laugh, others worry too much with the intention of calling the police, others masturbate and others conclude that it is a joke in very bad taste. They are key in the final work. The co-authors of the piece. No Fun happens in real time and documents in video the two screens of both Internet users interacting with a third party: us, the spectators. A multi-screen triangle is created with the characteristic of offering diverse multi-temporal spaces. As an invasive and performative viral art, we are voyeurs, “the one who sees” an intimate moment of the many users who make up a past history which, however, invites and encourages us to reproduce new experiences just by clicking on the application:

Intimacy brings us back to ourselves, confronts us with the desire to be and with the failures of not having been, of not being. But intimacy also places us in the relaxation of an always prophylactic contact, away from: the material dangers, the responsibility of what is said, pollution, disease, procreation, commitments, the reproduction of daily life and its collective norms, although more than ever ruled by desire. (Zafra, 2008, p. 141)

The Argentinian critic Beatriz Sarlo (2005) affirms that all discourse on the past already contains an anachronistic dimension, where history itself is persecuted by anachronism and its limits must be recognized and traced (p. 78). Sarlo, welcomes the ideas of the art historian Georges Didi-Huberman who studies these issues extensively, and states that the images do not belong to the time in which they were produced: “In accordance with Jacques Rancière, Huberman suggests that these objects place us in front of a time that goes beyond the frames of a chronology” (Sarlo, 2005, p. 81).

The historian François Hartog exposes the current problematic in which one speaks more of past than of history. So the past and memory are united: “Memory is evocation, summoning, appearance of an element of the past in the present and, above all, memory is an interested use of the past” (Silva, 2012, p. 210). Hartog declares that it is since 1980 that memory has played a relevant role together with booming heritage policies and the identity issue: “These notions are signs that we were aware that something had changed in our relationships over time” (p. 211). The concept of “anachronism,” paraphrasing Ranciére (2015), is unhistorical because it blurs the same conditions that make up all historicity. There is history in relation to the ruptures that individuals cause in their time. That is why you cannot blame the historian, but eliminate the idea of anachronism as error in time (Didi-Huberman, 2008, pp. 57-58):

To the extent that they act in violation of “their” time, in violation of the temporality line that puts them in their place by forcing them to “use” their time in one way or another. But this break is only possible due to the possibility of connecting this line of temporality with others and owing to the multiplicity of temporality lines present in any “one” time. (2015, p. 46)

Rancière and Huberman (under the theoretical influence of historian Marc Bloch), seem to agree that there are anachronic modes of connection: events, ideas, happenings and symptoms contrary to time, out of any contemporaneity and identity of time with “itself.” Leaving “your” time causes numerous temporalities that help us tell the story. Thus, historical time is a complex symbiosis of what belongs and what is transformed (Didi-Huberman, 2008, pp. 63-65). Huberman affirms Rancière’s following statement: “The multiplicity of temporal lines, of the same senses of time included in the ‘same’ time are the condition of historical activity” (2008, p. 56). Hartog, in this regard, expresses his concern because:

These are complex issues that are difficult to untangle, for many reasons, but in particular because of the multiple and related time scales that are involved: the immediate, the local, the regional, the global, all at once, and in a time almost without end. (…) Our current ways of acting in time and over time do not seem able to face the situation. There are hardly any instances to manage such types of time and put the necessary policies in place. (Silva, 2012, p. 211)

Time and its relation to anachronism are affected by what Huberman exposes as a “symptom,” that which interrupts the course of chronological history. And in the image, that which interrupts the normal course of representation. Therefore the aesthetics of the symptom is what is lacking, what is not shown. The Colombian critic Maria Cecilia Salas Guerra declares that the anachronic image is also symptomatic, of unfamiliar presence. A non-visible, unknowable being that gives rise to an image that opens onto something that has not yet been classified. The discipline of art history, analysing the author Huberman, has this not-knowing as problematic and makes it the anticipation, the opening of a new knowledge (Salas Guerra, 2016, p. 51):

In the already long career of the French author, one can read the insistent counter-themes that contribute to a particular counter-history of art, which vindicates the image in counterpoint with the Western-Italian notion of art (…). From there it is possible to say more about the image, beyond the tyranny of art itself as it was instituted since the Renaissance. It is about thinking of the image from the substrate of the flesh, of what is real not symbolizable, of the visual-virtual, of the piece that always escapes (…) of the dream image, of the tear and the symptom that interrupt where they are least expected. (p. 54)

The image therefore is classified by the historian, as well as the text. And so it has been agreed on its course throughout the history of art. But as Huberman argues, there is still no criterion that allows us to know how to order them. The archive, in the case of the image, is fundamental since it determines the form of historicity. And if we continue with a linear, chronological account, it is not possible to build a true story. In an interview with Huberman, we read: “For the simple reason that a single image —as well as a single gesture— gathers heterogeneous times in itself. In order to historicize the images, we must create an archive that can not be organized as a pure and simple story” (Romero, 2007, p. 19).

It is worth highlighting the successful thesis that the author exposes when comparing the complexity of cataloguing these images with the intention of contributing to the historical archive and the artistic manifestations of the 1920s and 1930s, where at the same time as historians placed this problem at the centre of their thought (Walburg, Benjamin, Bataille, etc.), avant-garde cinema emerged with new proposals for editing (Eisenstein, Kulechov, Brecht, Vertov and the Russian formalists): “Benjamin said that a true history of art should not tell the story of the images, but access the unconscious of sight, of vision, something that can not be achieved through the story or the chronicle” (p 19). Within this complexity, outlining historical trajectories has been the objective of the theorist Lev Manovich. He states that they have worked for many centuries and that, in his opinion, many changes in image during the nineties are recreated in the old ways, but in digital format: “It is difficult to establish these analogies, but you could say that we are where cinema was in 1905: there was already a certain language, but a few years later something different appeared” (Manovich, 2004, p. 14).

Figure 2. Final scene of the film The Great Train Robbery (1903), by filmmaker Edwin S. Porter.

Going back to the work No Fun, it is important to bear in mind the author Manovich, who maintains that new media allow the user a random access and in analogy, some of the cinematographic machines of the XIX century also possessed this capacity. We live in an information society where we have to answer emails and consult thousands of data: “And maybe we would like to add some fiction and pleasure to it, perhaps an element of surprise too” (Manovich, 2004, p. 16). The montage and performance of the Mattes’ work requires an exhaustive comparison between the cinematographic critique and its relation with new media, which the author already widely collects in the exemplary book The Language of the New Media of Communication: The Image in the Digital Era (2006). Summarising, we must remember the phenomenon of Lev Kuleshov’s cinematographic experiment during the 1920s and his three montage interpretations —creating the term “creative geography” as the coherent, visual, narrative capacity and the effects (and experiences) arising from various montages. Or Edwin S. Porter in the movie The Great Train Robbery (fig. 2), the beginning of the western in 1903. Porter knew masterfully how to manipulate the viewer with the technique of montage in his last scene: the close-up of a gunman, the actor Justus D. Barnes and head of the gang, who aims and shoots the spectator at point-blank range. This action caused the same exaltation in the public as the Lumière brothers’ train in 1985: a locomotive appears from the background of the screen while more than one spectator jumps from his seat to run. The cinema, the analogue and digital media are closely linked to the spectacle and the use of leisure activities. And we demand entertainment and surprise. Remember also the historical radio episode, although in this case it is a sound information medium, The War of the Worlds radio adaptation starring Orson Welles in 1938, which caused extreme moments of panic in New Jersey and New York.

These are some examples of the influence of new images on the eyes of the audience. Every innovation in visual aesthetics seems to hide some magic. And each new visual technology implies a social literacy: a determined time of reflection and a collage of its possibilities hand in hand with the consumers until they establish themselves as everyday. The film and new media critic Jorge La Ferla states that the audio-visual field, since the creation of photography to the current crisis of post-cinema, has always been accompanied by the novelty effect (La Ferla, 2010, page 152). Cinema after the cinema or expanded cinema. Expanded Cinema, filmmaker Stan Vanderbeek’s term that the author Gene Youngblood picks up in his valuable 1970 publication expressing that video, digital and electronic images were also art. A point of inflection in the history of art and of great influence in the publications of Radical Software —the magazine had many contributions from various disciplines such as physics, anthropology, psychology and art theory— or the Californian Ant Farm group that gave rise to the controversial Media Burn intervention of 1975, in which the artists crash a Cadillac against a pyramid of televisions, thereby denouncing a deep criticism of the American television culture and the “passivity of the viewer”:

Another determining fact that so far has only been studied a little, is that the consumption of cinema will be largely locative, its transmission on line / Wi-fi, on demand (…) prevailing. The inevitable transfer to digital conversion raises relevant issues related to the economy of numerical information and its mathematical processes and how to conceive its management from a metadata, in the form of algorithmic calculation. Perhaps the crucial issue is no longer to simulate the archiving and preservation of analogue media with the new supports, but to investigate ways of putting those databases into play, in a conceptual relationship. Information as such needs an economy (…) to be interpreted. (La Ferla, 2010, p. 158)

In the same way that La Ferla raises a need to know the different languages of communication and the readings that digital media offer in more detail, Manovich is interested today in the effect of computers on culture and users: how do we react to screen culture and the new modes of perception and cognition? It was in the nineties when there was a certain cultural and economic “convergence” of the film, television and computer industries (think of video games). According to the author this happened: “Because the real entertainment industry (which is a large part of mass culture, at least in the US) is cinema and television, not books, although many books continue to be sold.” (Manovich, 2004, p. 14) The works generated from online media, according to La Ferla, are usually consumed within a box on the computer screen. It is an immense offer of visual content on the Web that works like a window, where everything is within reach, in contrast to the usual difficulty of accessing materials decades ago (2010, p. 158).

The artists Eva and Franco Mattes interrupt and use personal computers randomly, through the media and through the media and economic power of art to investigate issues such as authorship, originality, security and privacy, and thus disrupt a society overloaded and over-stimulated by images. No Fun skilfully subverts the connected mass media in order to revive a mentally collapsed society, under the conditions of intense instability characteristic of post-Fordism (Fisher, 2016, p. 69). Like the subversive art of the International Situationist or the Dada movement, the Mattes launch provocations to the world to infect current standards and provoke a moment of doubt. (Carroll and Fletcher, 2012)

Concluding, the Zafra analysis (2008) is considered very successful, in which it is affirmed that there is still a clear separation of the meaning of the online body and the offline body, the latter referred to by the author as the “body” after the Internet” (p. 143). What supposes a rupture of the plurality of images of the “I” of the virtual world. This digital and connected media provides that which is reflexively repressed and silenced in cyberspace in which they assault different forms of dialogical, temporal and historical production within a permanent (e-)anachronism. The reversibility with effects, that is to say, a reflexive affectation of our experimentations on the Internet, is material of artistic interest: “This, to a large extent, centres the work of many parody artists who put themselves and put us in the place of the ‘other’, not as mere empathy but as something deeper that leads us to ‘be’ the other” (p. 142).

Conclusions

When computer systems and telecommunications converge, new possibilities for the artist take place. The place of action is an interactive space in which the location of the participants is not relevant, according to Ascott. There are no limits of space or time, so that they cease to be linear (Kac, 2010, p. 79). Since 1996, the wide acceptance of the Internet has led to the proliferation of autonomous hypermedia works that use this medium to communicate and express themselves globally. Faced with these artistic tendencies, Ascott affirms that although the practice of art will move from pixels to molecules, the artistic process will follow the path towards connectivity (between minds and systems) to immersion in data or the field of nanotechnology: “Interactive scenarios must still be planned that lead us to the transformation of matter and mind, and the rethinking of consciousness” (Ascott, 2000, p. 5). This syncretic trans-disciplinarity represents artistic research at all levels. That’s why we artists look in all directions for inspiration and understanding. Castrillón exposes that temporary disorder is characteristic of the artistic construction that helps to recreate spaces and memories in a reconstruction of the autofictional “I” (Castrillón, 2011, p. 60).

From this reflection, it is necessary to add the need to establish more debates about the artistic production of our days, which build new mechanisms in the generation of knowledge questioning the very figure of the artist in society, the objectual production of art, the system of art and its institutions and contemporary artistic research. Brian Holmes certifies the need to redefine the ways, means and objectives of a possible third phase of institutional criticism characterized by the notion of transversality, which helps to theorize about those experiments that occur far from the artistic circuit and its institutions (2008, p. 207). Let us think, for example, of the very present and requested citizen laboratories, fablabs, hackerspaces, biohackerspaces, as well as the DIY and DIYbio learning and production philosophy, free software studies, e-learning, e-collaboration, etc.

As we have reviewed, with the rapid development of interactive technologies, traditional social concepts such as individualism and identity are transformed into the context of artistic production. Equally, the Colombian art theorist Felipe César Londoño declares, are the relations between the spectator of a work (or co-author) and its author. Dada or Fluxus seem to revive again, continues Londoño, and with them their creative searches on interactivity and participation, although at that time without the need for programming languages. All the avant-garde movements that evolved towards the concept of media art were related, in some way, to collaborative dynamics between artists, scientists or spectators, a central aspect in contemporary artistic production and in the organization of societies (Londoño, 2010, pp. 104-105). The author offers an interesting analysis about the relationship between the cinematograph and the computer, since the structural cinema establishes an intense link with the current practices of creation in digital media. The influential filmmaker Malcolm Le Grice defends the non-linearity of a narrative cinema, which would anticipate the intrinsic properties of technologies: direct or random access (p. 103)

I have been researching this topic for many years, and from an early stage I developed an openly antinarrative position, understanding the term in the same sense in which Dziga Vertov said that cinema was the opium of the people. In the first place, the narrative provides a sense of coherence that, in my opinion, is not there, it is not real. It is a false coherence, a summation of fallacious causes and effects. The world does not work like that, this is not how you experience it. (Cárdenas, 2008, p. 82)

The Internet, a priori, is a medium like television because it also contains audiences that share real or imaginary experiences over great distances. However, the interactive and participatory character of the Internet does differ from television: “The Internet is a new form of dialogue in the public space. (…) Without a clear direction, we move to an unexplored territory that holds great promise but presents great challenges” (Lovejoy, 1997, p. 223). The Internet involves the exploration of fundamental aspects of representation that have acquired new meanings such as content and context. Lovejoy affirms that today we understand how the context can alter the meaning of a work of art, while the Network is capable of creating great differences of conditions. The context on the Internet is linked to the content, which is activated and combined only when the participants turn on the screen and access them. There is, therefore, an inherent dis-location where the ideas of a context can highly influence a work of art on the Net (p. 223). Malcolm says that with the arrival of digital instruments the medium disappears, there is no longer a medium to dismantle. This relationship becomes much more complex: “I believe, therefore, that in each moment of life there is a confluence of forces that can only be accounted for by a kind of multinarrativity” (Cárdenas, 2008, p. 82).

Zafra highlights from cyberspace that different forms of identity reception and production converge in it, and it is in that diversity where reflection would be feasible unlike other media such as television: “As such we could still intervene on our time and on our subjectivity, to exceed the mere role of resigned bystanders and shaped bodies” (Zafra, 2008, p. 142). Television is illustrative, the images exposed and approved, the author continues, are not questioned.

Those that allude, not to a knowledge, nor to a present and active memory (more typical of reading and of some forms of browsing the web), but to emotions, identifications and projections, that is, to the past; and in the case that concerns us, to the repetition of identity models. (2008, p. 143)

Internet, is a virtual community where if the participants are not seen, then it becomes television, says sociologist Robert D. Putnam: “The Net has two possibilities: to become a television or a telephone. And the phone is to strengthen connections with those you know” (Pérez, 2003). We connect to avoid loneliness, the author points out, to escape from ourselves. This will mean a loss of empathy, ties and personal social capital.

The coexistence of unequal times in the anachronic (e-)temporality and a body in online and offline duality. Our biological condition cannot yet penetrate the immateriality of cyberspace, and that is why we suffer numerous tensions and uncertainties. In the same way that restlessness, doubt, nervous laughter or alarm penetrates us contemplating the Mattes’ work No Fun or, in the past, the effects of that last and direct scene of The Great Train Robbery, we are constantly submitted to the, for now, unpredictable and multiple languages of image and identity on the Net, and their infinite translations. With its heterogeneous times or, as Huberman designates, polychronic times. We live, mainly, in anachronic spaces uncomfortably feeling the multi-temporality. Inevitably connected.

Referencias / References

Ascott, R. (2000). Moistmedia, technoetics and the three VRS. En Tenth International Symposium on Electronic Art (ISEA), París. Recuperado de http://www.isea-webarchive.org/content.jsp?id=36400

________ (2005). Syncretic reality: Art, process, and potentiality. Drain, 5, páginas no numeradas. Recuperado de

http://www.drainmag.com/contentNOVEMBER/FEATURE_ESSAY/Syncretic_Reality.htm

Bermejo, D. (4 de febrero de 2017). Sextorsión, el chantaje que sufren aquellos que practican sexo virtual. El Mundo. Recuperado de http://www.elmundo.es/f5/comparte/2017/02/04/58936cb1468aeb31118b4677.html

Castells, M. (2014). El impacto de internet en la sociedad: una perspectiva global. OpenMind. Compartiendo conocimiento para un futuro mejor. Grupo BBVA. Recuperado de https://www.bbvaopenmind.com/articulos/el-impacto-de-internet-en-la-sociedad-una-perspectiva-global/

Castrillón, A. (2011). La temporalidad anacrónica de El río del tiempo de Fernando Vallejo. Estudios de Literatura Colombiana, 28, 59-75.

Cárdenas, J. S. (2008). Antinarratividad y humanismo. Entrevista con Malcom Le Grice. Minerva. Revista del Círculo de Bellas Artes, 9, 80-83.

Carroll, J. y Fletcher, S. (comunicado de prensa, 2012). Recuperado de https://www.carrollfletcher.com/usr/documents/exhibitions/press_release_url/7/eva-and-franco-mattes-anonymous-press-release.pdf

Burke, P. (2010). Hibridismo Cultural. Madrid: Ediciones Akal.

Deutsche, R. (1996). Evictions: Art and Spatial Politics. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Didi-Huberman, G. (2008). Ante el tiempo. Historia del arte y anacronismo de las imágenes. Buenos Aires: Adriana Hidalgo Editora.

Fisher, M. (2016). Realismo capitalista: ¿No hay alternativa? Buenos Aires: Caja Negra Editora.

Holmes, B. (2008). Investigaciones extradisciplinares. Hacia una nueva crítica de las instituciones. En Producción cultural y prácticas instituyentes. Líneas de la ruptura de la crítica institucional, (pp. 203-215). Madrid: Traficantes de Sueños.

Kac, E. (2010). Telepresencia y Bioarte. Interconexión en red de humanos, robots y conejos. Murcia: Cendeac.

La Ferla, J. (2010). Cine expandido o después del cine. En Ejes de Reflexión. Desafíos de la cultura en la “era digital,” (pp. 152-159). Instituto de Políticas Culturales Patricio Lóizaga, Buenos Aires: Universidad Nacional Tres de Febrero.

Londoño, C. F. (2010). Producción artística y nuevas tecnologías. Errata. Revista de artes visuales, 3, 92-117.

Lovejoy, M. (1997). Digital Currents: Art in the Electronic Age. Nueva York: Routledge.

Manovich, L. (2004). Definitivamente, creo que estamos en el principio. Artnodes: revista de arte, ciencia y tecnología, 3, 12-19.

Pérez, P. (2003). Robert D. Putnam. Muy Interesante, 271. Recuperado de https://www.muyinteresante.es/historico/articulo/robert-dputnam

Rancière, J. (2015). The Concept of Anachronism and the Historian’s Truth (English translation). InPrint, 3, 1, 21- 52. doi:10.21427/D7VM6F. Recuperado de https://arrow.dit.ie/inp/vol3/iss1/3

Renán, S. (2012). Memoria e historia: entrevista con François Hartog. Historia Crítica, 48, 208-214.

Roland, R. (2000). Globalización: tiempo-espacio y homogeneidad-heterogeneidad. Zona abierta, 92-93, 213-242.

Romero, H., Schmitt, M., Fernández-Savater, A., y del Castillo, R. (2004). Posmodernidad y globalización. Entrevista a Fredric Jameson. Revista Archipiélago, 63, 1-11. Recuperado de https://biblioweb.sindominio.net/pensamiento/jameson.pdf

Romero, P. (2007). Un conocimiento por el montaje entrevista con Georges Didi-Huberman. Minerva: Revista del Cículo de Bellas Artes, 5, 17-22.

Salas, M. C. (2016). Latencias de la imagen: anacronismo y síntoma. Revista colombiana de pensamiento estético e historia del arte, 4, 41-79.

Sarlo, B. (2005). Tiempo pasado. Cultura de la memoria y giro subjetivo. Una discusión. Madrid: Siglo Veintiuno Editores.

Silva, R. (2012). Memoria e historia: entrevista con François Hartog. Historia Critica, 48, 208-214.

Zafra, R. (2008). Conectar, Hacer, Deshacer (los Cuerpos). Zehar: revista de Arteleku-ko aldizkaria, 64, 138-145.

_______ (2011). Un cuarto propio conectado. Feminismo y creación desde la esfera público-privada online. Asparkía. Investigación feminista, 22, 115-129.

Webs

Eva y Franco Mattes:

https://0100101110101101.org/

http://www.cccb.org/es/participantes/ficha/eva-franco-mattes/40231