|

“Internet no es sólo una herramienta que debe ser usada en la educación, sino una nueva manera de educar. Es decir, un recurso pasa a ser referencia de educación, exigiendo un trabajo coherente con su manera de organizarse, de existir.”(Vegara Nunes, 2002)

El siguiente artículo propone el uso de las páginas web como herramienta interdisciplinar en la clase de Inglés con fines Profesionales y Académicos. El conocimiento de Idiomas junto con la Informática son las áreas de conocimiento que los titulados de la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid necesitan estudiar, como complemento a la educación recibida durante la carrera, con el objetivo de facilitar su incorporación al mundo laboral[1]. Una asignatura optativa de lengua inglesa que utilice la informática puede acercar al estudiante a cubrir de una forma más completa su formación futura. Las páginas web como pretexto interdisciplinar nos han servido para trabajar con un grupo de alumnos con un nivel de inglés heterogéneo. La motivación y el éxito de las actividades realizadas demuestran la utilidad de compaginar el estudio de idiomas con otras disciplinas.

Páginas web, enfoque cognitivo, comprensión lectora, inglés con fines específicos, aplicación didáctica.

Introducción

La utilización de las páginas web en la clase de inglés para arquitectos supone, por las peculiares características propias del colectivo de arquitectos tanto en el plano académico profesional como cognitivo, una herramienta que nos ha de permitir mejorar su aprendizaje del idioma. A continuación se enumeran los aspectos por los que consideramos adecuado ente enfoque.

· Los resultados de un estudio llevado a cabo por el C.O.I.E. (Centro de Orientación Información y Empleo) durante el curso 1999-2000. En este estudio, destaca que de los titulados de la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid del curso 89/99, y con el objetivo de facilitar su integración en el mundo laboral, un 63% complementó la formación recibida en la Universidad con estudios de idiomas, y un 64% lo hizo con estudios de informática (GESE-UPM, 2000:20)[2]. El binomio idiomas e informática se consolida como un refuerzo imprescindible para el mayor número de titulados, por lo que desde el punto de vista de la docencia dentro del sistema que forma a los futuros titulados, se debería encontrar un modo de ayudar a completar la formación que ellos mismos consideran complementaria para facilitar su incorporación al mundo laboral.

· Internet es asimismo uno de los medios preferidos por los estudiantes de Arquitectura para la difusión y conocimiento de la Arquitectura. En el curso académico 98/99, una encuesta a nivel nacional entre estudiantes de arquitectura (Arquitectos, 1999:38) lo situaba ya como el tercer medio en orden de preferencia, por detrás de los Libros (primer lugar) y las Revistas (segundo lugar).

· En este sentido, una encuesta realizada en 2001 a mis alumnos que escogen la asignatura de “Aplicaciones Profesionales en Inglés para Arquitectos”, en la Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid (ver figura nº1), indica que el uso de Internet está ya generalizado; todos ellos utilizan Internet, con un grado medio de uso (6 en una escala del 0 al 10). El 50.8% del uso se destina a temas de la carrera; y dentro de este tipo de acceso, los estudiantes indican que el 56.5% de las páginas aparecen en Inglés. El porcentaje de uso de Internet es puede considerar elevado para estudiantes de muy diversas procedencias sociales; significa por un lado que todos tienen acceso a un ordenador personal (sea en casa o en la Universidad) y por otro que lo usan para acceder a Internet con asiduidad. Ello indica claramente un alto grado de introducción de este medio de comunicación y acceso a la información entre nuestros jóvenes estudiantes de Arquitectura. En promedio, más de la mitad del tiempo de uso de Internet está relacionado con la carrera, lo cual indica que es una herramienta útil para el desarrollo de la misma. Y la mayoría de las páginas accedidas por los estudiantes cuando buscan temas de Arquitectura están escritas en Inglés. Esto reafirma la importancia del idioma en la profesión y en especial en la navegación Internet relacionada con Arquitectura.

|

Figura nº 1

· La enseñanza multimedia, y en general la adquisición de conocimientos a través de varios medios de comunicación simultáneos (en el caso de las páginas web: texto, imágenes, e incluso sonido) supone un aumento considerable de la capacidad de asimilación y retención de conocimientos.

· Los estilos de aprendizajes del colectivo de estudiantes de arquitectura demandan un tipo de enseñanza enfocado al uso de la imagen como técnica y recurso práctico de aprendizaje, y de forma muy destacada, un aprendizaje que conlleve actividades prácticas.

· Los arquitectos son sin lugar a dudas el colectivo que más se comunica con imágenes. Su propio plan de estudios se compone de asignaturas donde se enseña al alumno a mirar y observar, tal es el caso de Ideación Gráfica, Análisis de Formas o Historia del Arte, entre otras.

· Desde un punto de vista de investigación futura la creación de las páginas web dentro del mundo de la arquitectura han supuesto y supondrán una nueva forma de compartir información a la vez que una nueva forma de lenguaje comunicativo entre arquitectos. El arquitecto no queda relegado a su obra ni a su estudio. Con la aparición de las páginas web se crea un medio para mostrar proyectos. La mera fotografía de un proyecto dentro de un colectivo determinado de arquitectos que comparten un mismo mapa cognitivo supone una forma de comunicación.

· Desde el punto de vista de la lingüística se vislumbra por la bibliografía emergente y por las necesidades futuras del mercado como una herramienta mediante la cual el profesor de lenguas compartirá un nuevo enfoque para la enseñanza de una lengua extranjera (Crystal, 2001). Internet abre nuevos campos en el terreno del E.S.P.[3]

Los aspectos anteriores motivan el enfoque planteado en este trabajo; la metodología propuesta se adapta al proceso y estilo de aprendizaje de los alumnos, lo maximiza, y les motiva en tanto en cuanto su interdisciplinariedad les prepara para su incorporación al mundo laboral.

Fundamentación teórica

Los fundamentos teóricos para la actividad propuesta son eminentemente de índole cognitiva, y con especial atención a los estilos de aprendizaje de los alumnos. Cualquier proceso educativo debe considerar la forma en que a los estudiantes les resulta más fácil adquirir conocimientos, para de esta forma mejorar la motivación y el grado de asimilación de lo enseñado.

Los estilos de aprendizaje se pueden definir como “cognitive, affective, and psychological traits that are relatively stable indicators of how learners perceive, interact with, and respond to their learning environment” (Reid, 1993: 56).

En el modelo de Reid (1995) se estudian las modalidades sensoriales de cada individuo (visual, auditivo, cinestésico[4] y táctil) y el factor dependencia-independencia de campo (individual y social), clasificando los estilos de aprendizaje en:

a) Estilo visual;personas que suelen reaccionar ante nuevas informaciones de forma visual o gráfica, es decir, con pensamiento espacial.

b) Estilo auditivo; personas que aprenden escuchando explicaciones orales, con pensamiento verbal.

c) Estilo cinestésico; personas que aprenden cuando se implican físicamente en la experiencia.

d) Estilo táctil; personas que aprenden mejor cuando realizan actividades manuales.

e) Estilo social; personas a las que les gusta la relación con el grupo, y aprenden trabajando en equipo y mediante la interacción con otras personas. Son dependientes de campo y prefieren mayor estructura externa, dirección e información de retorno.

f) Estilo individual; personas que prefieren trabajar solas y recuerdan mejor lo aprendido si lo han hecho por sí mismos. Son independientes de campo y prefieren la resolución personal de los problemas.

En el caso de los estudiantes de arquitectura españoles el estilo dominante resulta ser el cinestésico, es decir el que requiere acción (Úbeda 2002). El grupo de estilos secundarios lo forman el estilo Visual, Táctil, Auditivo y Grupal. Finalmente, el estilo menos desarrollado es el Individual.

El estilo Visual, a través de imágenes y gráficos, encuentra un medio ideal en Internet, donde no solamente abundan elementos infográficos, sino que en el caso concreto de las páginas web relacionadas con el mundo de la Arquitectura, abundan las fotografías. Adicionalmente, el texto escrito en las páginas web lleva asociada una dimensión gráfica del lenguaje. En este sentido, Crystal comenta:

“ The web in effect holds a mirror up to the graphic dimension of our linguistic nature. A significant amount of human visual linguistic life is already there, as well as a proportion of our vocal life.” (Crystal 2001: 195).

De hecho, la Web rompe todas las barreras para la representación del texto escrito; no solamente en cuanto a tipos de letra y tamaños, sino también a nuevas dimensiones como el color, el movimiento, la animación, y al hecho de que el texto no tiene por qué estar distribuido de forma lineal; el diseñador de la página puede ubicar texto donde crea más oportuno, y es el usuario quién decide la secuencia y el recorrido visual de la página web. Tal y como Crystal apunta, la Web se adentra también en el texto hablado, sea a través de archivos de voz o, de forma más integrada, de hipervínculos que ejecuten la audición de textos hablados asociados.

La enseñanza y el aprendizaje multimedia, por la combinación de diferentes medios de comunicación de forma integrada, goza de una excelente reputación como método de enseñanza en una época marcada por la falta de tiempo y la globalización, en el que tanto la enseñanza a distancia, el e-learning, y el autoaprendizaje en casa o en la empresa sin horarios rígidos son formas apreciadas de aprender. Desde una perspectiva cognitiva, es fácil comprender su potencialidad. Pero también existen aspectos determinantes asociados a los estilos de aprendizaje que pueden restar efectividad a esta metodología, y que deben ser cuidadosamente considerados.

Generalmente se asocia el término “multimedia” a la combinación de información visual y verbal; según Mayer (1997), el alumno posee un sistema de procesamiento de la información visual, y otro para la información verbal. En el aprendizaje multimedia, el alumno se sumerge en tres procesos cognitivos importantes:

1) Selección: es el reconocimiento del texto verbal base o de la imagen visual base.

2) Organización: la creación los modelos verbales o visuales correspondientes del sistema a aprender.

3) Integración: la creación de vínculos entre los dos modelos.

El modelo de Mayer propone, basándose en experimentos relacionados con la efectividad del aprendizaje, cinco principios básicos a considerar en el uso de multimedia para ayudar a los alumnos a comprender una explicación científica:

a) Principio de múltiple representación: es mejor representar una explicación en palabras e imágenes que solamente en palabras; basado en el proceso cognitivo integrador.

b) Principio de contigüidad: en una explicación multimedia, presentar las palabras e imágenes correspondientes de forma contigua y no separada.

c) Principio de atención repartida: en una explicación multimedia, presentar las palabras como narración auditiva y no como texto en la pantalla.

d) Principio de diferencias individuales: los principios anteriores son más importantes para los estudiantes con un bajo nivel y con alta capacidad espacial

e) Principio de coherencia: en una explicación multimedia, usar pocas palabras o imágenes ajenas.

Como he comentado anteriormente, el uso de nuevas tecnologías educativas debe complementarse con la consideración de los estilos de aprendizaje de los alumnos. En este sentido, puesto que el estilo dominante de los estudiantes de arquitectura es el cinestésico, una actividad de navegación en Internet, altamente interactiva, se adaptará perfectamente. La efectividad de un aprendizaje con esta herramienta queda garantizada, maximizándose la comprensión y la retención de conocimientos. En el caso que nos ocupa se trata del aprendizaje del Inglés con el apoyo de actividades con páginas web.

Así pues, la actividad de búsqueda que se propone se adapta al estilo cinestésico, puesto que supone una participación muy activa del alumno, en el que debe “navegar”, aunque sea en un espacio virtual, para llegar a la información buscada, y en nuestro caso, adicionalmente para aprender el idioma. Robinson (2001: 289) describe una actividad similar para ilustrar lo que él denomina “Task based language teaching”: la actividad es “finding a journal article in a library using library technology”.

La obtención de información e Internet es en realidad un proceso cognitivo con un alto grado de interactividad; cuando se busca algo en Internet, normalmente apoyándose en un Buscador (Search Engine) como Altavista, Google, etc., y en una interrogación (query) simple o avanzada (con operadores lógicos por ejemplo), se obtiene una información, que normalmente no es exactamente lo que se buscaba, y cuyo grado de relevancia para la búsqueda se pone de manifiesto en una subsiguiente interrogación al Buscador, con las variaciones adecuadas (más específica, más precisa, nuevas palabras clave, etc.). Este proceso que Belew (2000) denomina Relevance Feedback se corresponde con un Reconocimiento de Objeto, en el que el objeto que debe ser reconocido es una representación interna de un documento prototípico, en el sentido cognitivo de prototipo de Rosch (1976), que satisface las necesidades de información del navegante. El proceso de feedback continúa de forma iterativa hasta que finaliza la búsqueda, con un grado mayor o menor de satisfacción. El proceso varía en numero de iteraciones no solamente en función del tiempo disponible sino muchas veces en función de la criticidad de la búsqueda; así por ejemplo, un abogado buscando jurisprudencia para uno de sus casos, o un médico buscando posibles soluciones a un problema, o un investigador asegurándose de que nadie ha trabajado en su línea, o un arquitecto buscando una descripción de una técnica innovadora, dedican un ciclo de iteraciones claramente superior al de un estudiante que busca una información para incorporar a un trabajo de clase, o alguien que simplemente siente curiosidad por un tema y busca algo de información.

En el proceso de búsqueda de documentos existen además dos dominios conceptuales en el sentido cognitivo de Lakoff (1987): el del usuario, y el de los autores de los documentos. El primero se refleja en ese prototipo y en la forma en que se expresa en la búsqueda mediante palabras que lo puedan describir. El segundo se expresa en las palabras claves asociadas al documento generado, que pueden depender muchas veces no solamente del mapa cognitivo del autor, sino también del contexto y del tipo de publicación a que va destinado (divulgación, especializado, etc.). Un mismo documento puede ser caracterizado por su autor con diferentes palabras clave en función de estos parámetros. Un mismo concepto puede expresarse o un documento puede desarrollarse con palabras distintas en función del género lingüístico al que pertenece (artículo científico, artículo periodístico, etc.) y su registro y vocabulario asociado. Entre medio está el Buscador, que de una forma eficiente actúa como un puente entre ambos dominios, y que apoyándose en una potente plataforma tecnológica y en sofisticados algoritmos que incluyen técnicas de Inteligencia Artificial, debe ser capaz de minimizar el tiempo de obtención de la información (Information Retrieval), y en la medida de lo posible, aprender del usuario y de su mapa cognitivo a través del Feedback de Relevancia.

En este sentido el proceso de lectura se realiza utilizando las técnicas de scanning (lectura superficial y rápida con el fin de localizar una información determinada.) y skimming (lectura rápida superficial cuyo objetivo es extraer la idea general, la esencia del texto). En ambas técnicas la lectura adquiere un papel importante en un género que procede de una fuente multimedia.

A su vez, las páginas web nos permiten acceso a textos genuinos auténticos en el sentido en el que Durán (1999: 199) clasifica los textos; genuino en el sentido de especialidad, y auténtico en el sentido que es útil para la enseñanza del idioma. Las ventajas, inconvenientes y los usos recomendados que Durán indica son:

|

Texto |

Ventajas |

Inconvenientes |

Uso recomendado |

|

Genuino auténtico |

- Interesa al alumno por su propio contenido - Motiva y proporciona sensación de logro al dominarlo - Existe una gran variedad donde elegir - Pone al alumno en contacto con el lenguaje científico real |

- puede tener longitud excesiva - puede utilizar conceptos muy elevados para los alumnos y el profesor de idioma - si no se dominan las estructuras del lenguaje, dificulta su presentación ordenada |

- Nivel intermedio e intermedio alto - Nivel avanzado |

La importante dimensión cognitiva del proceso de búsqueda comentada anteriormente, debe combinarse con el uso adecuado del lenguaje para, con la flexibilidad necesaria de registro lingüístico del alumno, utilizar Internet de forma efectiva. Será necesario pues desarrollar ese aspecto del alumno, que podrá practicarlo de forma motivadora en la búsqueda en la Web.

A continuación veremos la actividad que se propone, fundamentada en los conceptos anteriores.

Ejemplo de actividad

La actividad que a continuación presentamos se desarrolla dentro del modulo número uno de la asignatura optativa de “Aplicaciones Profesionales en Inglés para Arquitectos”. Esta asignatura es de cinco créditos y se imparte en el primer y segundo cuatrimestre en la Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid. Los alumnos que escogen la asignatura están en el segundo ciclo de sus estudios de arquitectura. El nivel medio de conocimiento de Inglés que este grupo viene teniendo hasta la fecha corresponde a un grupo con un nivel que oscila de intermedio a avanzado. Como ejemplo, en este artículo proponemos un ejercicio para trabajar con unas páginas web de un nivel intermedio. Sin embargo, en la bibliografía proponemos algunos ejemplos de otras páginas web niveladas para alumnos de nivel intermedio alto y avanzado.

Para una correcta descripción de la actividad, que facilite la comprensión así como su aplicación real, se presenta a continuación tres fichas: una de programación en el aula, otra de la unidad didáctica en sí y una de contextualización genérica dentro de la asignatura. La primera en español, corresponde a una ficha contextual en la que se puede observar cómo la fundamentación teórica expuesta en este trabajo se adecua a la actividad propuesta. La segunda en inglés, corresponde al desarrollo de la actividad en tiempo de realización real en el aula. Para finalizar, la tercera en Inglés correspondería a la unidad completa en la cual se recoge en grafía azulada las actividades de la unidad que aquí exponemos.

1. Ficha Contextual

Área: INGLÉS |

Curso: APLICACIONES PROFESIONALES |

|

Bloque temático I: |

Temporización: Primer y segundo trimestre |

|

UNIDAD DIDÁCTICA: “Working and learning through web pages”.

|

|

|

Objetivos didácticos: - Objetivo general de etapa: desarrollar la comprensión lectora. - Objetivo general de área: activar un registro propio del entorno de trabajo.

Al finalizar esta unidad, los alumnos deberán ser capaces de: - Distinguir las estructuras de un registro formal de un entorno de trabajo. - Valorar las opiniones de sus compañeros. - Identificar las expresiones metafóricas como medio para transmitir sus pensamientos e ideas. |

|

|

Criterios de evaluación: Al finalizar esta unidad, el alumno deberá demostrar que: - Relaciona estructuras y verbos de un registro básico con otras de registro más apropiado para el entorno de trabajo; - Confecciona frases que expresan las ideas que tienen sobre un proyecto, edificio o casa; - Es capaz de entender las imágenes que otros arquitectos poseen de sus proyectos; - Enumera aquellos aspectos importantes que debe tener en cuenta al describir proyecto. |

|

|

Conceptos: 1. Tipos de proyectos 2. Partes que lo componen 3. Planta y alzado |

|

|

Temas transversales: - La percepción en arquitectura

|

|

|

Procedimientos: - Identificación de un género cotidiano de consulta - Identificación de vocabulario específico arquitectónico en inglés - Análisis y comentarios en inglés de edificios conocidos - Realización de descripciones en Inglés sobre diferentes proyectos

|

|

|

Capacidades: - Desarrollo del análisis de proyectos dentro de un contexto cotidiano en un entorno de trabajo - Desarrollo de la imaginación en un ambiente de recreo. - Desarrollo de la actividad mental en torno a entidades comunes entre los arquitectos. |

|

2. Ficha de desarrollo de la actividad

LESSON PLAN

|

Course: 2001-2002 |

Subject: Professional Applications in English for Architects |

Group: A

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Class: SX5

Timing:3h |

Date: |

No. Students: 24 |

Topic: “Working and Learning though web pages”. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Aims:

Ø Scan and skim web pages focused on professional projects.

Ø Use language to effectively convey information and "ideas" in a straightforward working situation at Practice.

Ø Take an active part in a group discussion, constructively contributing to the sustained development of the project.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Procedure:

A. Students are taken to the computer’s room and are asked to browse the web page http://www.fosterandpartners.com B. The teacher asks them to choose and read carefully one project they like the most.

C. The teacher asks the students to check with their classmate those words or sentences they don’t understand. If they still have any doubt they ask their teacher.

D. Now, the teacher asks them to browse the web page http://www.calatrava.com

E. The teacher asks them to choose and read carefully one project they like the most.

F. The teacher asks the students to check with their classmate those words or sentences they don’t understand. If they have still any doubt they ask their teacher.

G. Brainstorm. 1. Students say things both pages have in common. 2. Students say things both pages don’t have in common. In both cases, the students justify their answer.

(Break) First session

H. Students browse new web pages according to their Architect’s preferences. The aim is to find a Practice with summer vacancy jobs for students where they can apply for.

I. The teacher assigns homework to the students

|

Time: 3 h.

15'

15'

15'

10'

10'

5'

15-20'

20'

30-40'

10'

|

|||

|

|

||||

|

Materials & Aids:

¨ Computer’s room ¨ Set of photocopy “Working and learning through web pages”.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Homework:

Students will choose a project to be printed from any web page they have browsed in class. Then they will look for the same project text in an architectural magazine or journal. After reading both of them they will classify them in the same way: unknown vocabulary; vocabulary considered as specific for architects; metaphors and sentences or grammar structures they consider complicated.[5]

|

||||

3.Ficha de la unidad organizativa completa en la que se enmarca la actividad.

Subject “Professional Requirements in English for Arquitects”

LEVEL: Intermediate

|

UNIT PLAN |

Lesson 2 Working and learning through web pages

|

|

LEAD-IN |

Contrasting well-known macro-international Practices on the web pages. Description/discussion/comparison |

|

TEXTS |

Webs: Norman Foster Santiago Calatrava |

|

LISTENING |

Tape: London´s Changing face |

|

COMMUNICATIVE ACTIVITY |

Express and react an opinion about a project |

|

WRITING |

Describe a project you like |

|

GRAMMAR |

- Review of present perfect.

- Phrasal verbs |

|

VIDEO |

1. N. Foster Practice. (53m)

2. Babel 2015 (25m.) |

|

TIMING |

3 weeks |

|

EVALUATION |

Dossiers on web pages visualising specific vocabulary |

Evaluación

La evaluación –como señalan Alcaraz & Moody (1983)- está estrechamente vinculada a los objetivos, ya que las diferentes pruebas que evalúen el rendimiento del estudiante deberán indicar qué objetivos se han cumplido y cuales no. Entendemos que esta relación entre evaluación y objetivos es extraordinariamente útil tanto para el estudiante como para el profesor. La evaluación de la comprensión lectora tiene como principal objetivo conocer la capacidad del alumno para entender un texto escrito. Igualmente, hay que considerar las destrezas cognitivas (Marín 1989:42) que se le exigen al alumno: “capacidad de comprensión, de razonamiento lógico de conocimiento del mundo, etc. Al finalizar este ejercicio se le presenta al alumno un texto de un proyecto obtenido de una página web de un estudio de arquitectura conocido y se formulan preguntas que pueden ser de estilos diferentes (frases de verdadero/falso, de elección múltiple o preguntas propiamente dichas sobre el texto). Igualmente, se presentará al alumno tareas de distinción entre informaciones y opiniones, de identificación de referencia y alusiones no explícitas en el texto con relación a otros proyectos. Se plantearán también tareas de comprensión del vocabulario, de búsqueda de sinónimos y antónimos e incluso se les pedirá que identifiquen las metáforas que aparezcan.

En el ejemplo de trabajo con páginas web que hemos expuesto en este trabajo, el alumno presentará un dossier en el que se recogen los ejercicios para su evaluación. La actividad de tarea a realizar en casa o homework que se recoge en el anexo es solo una parte de este dossier .El profesor, al comienzo de cada unidad, distribuye en el aula un set de fotocopias en el que se recogen abundantes ejercicios de los mencionados anteriormente.

Conclusiones

El uso de Internet en la clase de Inglés para estudiantes de Arquitectura mediante la actividad descrita consigue motivar enormemente a los alumnos, que sin ser conscientes de ello, satisfacen las necesidades de sus estilos particulares de aprendizaje, trabajan con textos genuinos auténticos, y asimilan la información multimedia que reciben mientras practican con el vocabulario, sus diferentes registros léxicos y la flexibilidad en la definición del prototipo buscado según el proceso cognitivo descrito.

La actividad descrita desarrolla principalmente la destreza de comprensión lectora, y debe englobarse en una unidad didáctica que contenga otras actividades relacionadas con las búsquedas en Internet realizadas. Al finalizar esta unidad, y con el objetivo de sacar el máximo partido de un bloque didáctico coherente, los alumnos deberán haber realizado, en sesiones posteriores, actividades relacionadas con las cuatro destrezas siguientes:

- Comprensión lectora (la actividad de búsqueda en Internet)

- Expresión escrita

- Comprensión auditiva

- Expresión oral

La actividad propuesta tiene profundas raíces cognitivas, y ello facilita la asimilación y aprendizaje del idioma. Para aprovechar mejor sus ventajas, no debemos quedarnos ahí, sino que debemos complicar gradualmente la complejidad de la actividad, tanto en las páginas y el proceso de búsqueda, como en el contenido de los textos. Como comenta Robinson:

“...tasks making increasing conceptual/communicative demands increasingly engage cognitive resources, which progressively exploit learning mechanisms leading to greater analysis, modification and reestructuring of interlanguage, with consequent performance effects” (2001:301-302).

Por ejemplo en una o varias sesiones posteriores que pueden realizarse al final del curso.

Bibliografía:

- Alcaraz Varó, E. y Moody, B. (1983) Didáctica del Inglés: Metodología y Programación. Madrid Alhambra.

- Belew, R. K. (2001) Finding out about: A cognitive Perspective on Search Engine Technology and the www. Cambridge. University Press.

- Coll, J. F. (2001). “Making the most out of on-line multimedia resources to promote language learning in the English for Academic Purposes class”. En Francisco Fernández (Ed.) Los Estudios Ingleses en el Umbral del Tercer Milenio. Valencia: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universitat de València.

- Dudeney, G.(2000). The Internet and the Language Classroom. Cambridge. University Press.

- Durán Escribano, Mª P. (1999). Análisis y Evaluación del Texto Científico: Aplicaciones a la Didáctica de la Enseñanza del Inglés con Fines Académicos. Madrid. U.N.E.D. Tesis Doctoral inédita.

- Crystal,D. (2001) Language and the Internet. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press.

- Encuesta a estudiantes de Arquitectura de España 1998-1999. Fundación Caja de Arquitectos. Colección Arquithemas. Barcelona.

- Estudio sobre el Empleo de los Graduados de la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid Año 2000. Gabinete de Estudios Sociológicos y Estadística de la UPM. Rectorado de la U.P.M.

- Lakoff, G. (1987). Women Fire and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveals about Mind. Chicago. Chicago University Press.

- Marín J. (1989). Testing y Evaluación. ¿Por qué y qué examinamos? Revista de la Escuela Oficial de Idiomas de Madrid, 7: 40-47.

- Mayer, R.E. (1997). “Multimedia Learning: Are we asking the right questions”. Educational Psychologist Journal, 32, 1-19.

- Reid, J.M. (1993). Teaching ESL Writing. New Jersey. Prentice Hall Regents.

- Reid, J.M. ed. (1995). Learning Styles in the ESL/EFL classroom. Heinle and Heinle Publisers, Boston.

- Robinson, P. (2001). Cognition and Second Language Instruction. Cambridge Applied Linguistics.

- Rosch, E.; Mervis, C.B.; Gray, W.D. y otros (1976). Basic Object in Natural Categories. Cognitive Psychology, nº 8, pp. 382-439.

- Turkle, S. (1996). Life on the Screen. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Negroponte, N. (1996). Beign Digital. London: Holdder and Stoughton.

- Úbeda, P.; Escribano, Mª L. (2002). Análisis de los Estilos de Aprendizaje en los Estudiantes de Arquitectura: Un Estudio Contrastivo. Actas del Congreso Internacional AELFE 2002 Sep 26-28.( en prensa)

- Vegara Nunes, E.L. (2002) La pedagogía de Internet. Una perspectiva en la enseñanza a distancia de lenguas extranjeras. Revista Electrónica de Estudios Filológicos www.tonosdigital.com núm.3 marzo 2002.

Bibliografía web sobre Internet:

http://isoc.org-internet-histoey-brief.html

http://elsop.com/wrc/h_web.html

http://puc.cl/curso-dist/infograf/reception

http://netvalley.com/intraweb.html

Bibliografía web utilizada en el ejemplo propuesto en clase:

1ª Parte

http://www.fosterandpartners.com

2ª Parte

http://interArchitects.com/english/architecture/architecture.htm

http://archinet.co.uk/index.html

http://europa.eu.int/comm/oof/work

Algunos ejemplos de bibliografía web utilizada por niveles

|

ESTUDIOS DE ARQUITECTURA

|

||

|

Nivel Intermedio |

Nivel intermedio-alto

|

Nivel alto |

|

famous.html

|

|

www.geocities.com/CapitolHill/ 2317/sullivan.html |

|

|

|

www.greatbuildings.com/architects/ Herzog_and_de_Meuron.html

|

ANEXO nº1 Cuestionario sobre el uso del ordenador

Computing habits

1. Have you got a computer at home?

2. What do you use it for?

3. Do you use a computer at the University? What for?

4. What do you know about Internet?

5. Do you use it at home?

6. Do you use it at the University? What do you use it for?

7. If you could use the computer in your English class, what would you use it for?

8. Do you think it will be useful for improving your English level? How come?/ In which way?

9. Name 10 thematic categories that you will be interested to use in your English class, and explain or give a reason for your choice.

-

-

-

-

-

-

10. Name some advantages of working with web pages in your optional subject “Professional Applications in English for Architects”

11. Now, name some disadvantages of working/using web pages in your English optional subject.

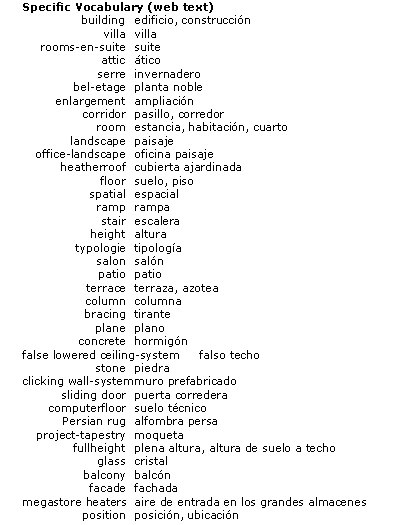

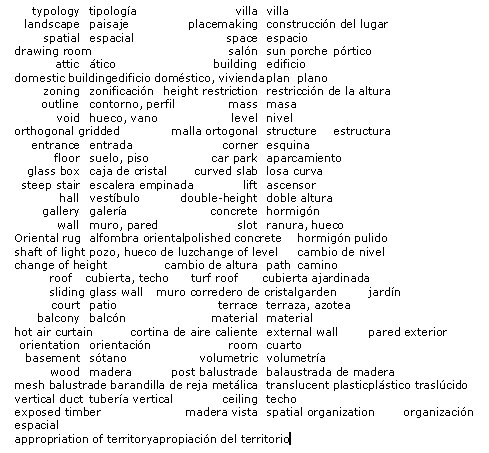

ANEXO nº 2 Ejemplo de trabajo de un estudiante.

Alumna: Lydia Mª Inglis Redondo

Página web consultada:www.mvrdv.archined.nl

Proyecto elegido: Villa Vpro de MVRDV Architects.

Coteja el proyecto con la revista especializada: Achitectural Review 1999 nº 1225

Textos de: VILLA VPRO en www.mvrdv.archined.nly VILLA VPRO enAchitectural Review 1999 nº 1225 pp.38-40

VILLA VPRO

For the VPRO, the dutch “artistic” broadcasting company, a new building means leaving the present condition of more or less 11 villas. Villas, which played throughout the years a vital role in the identity of the VPRO. People, who used to work in rooms-en-suite, attics, serres and bel-etages will have to find their spot in a new and “real” office-environment.

Should this existing identity be stopped? Can the present improvised use of space, which often had an influence on the programs that were produced, be combined with the required “efficiency” of modern office? And can this “loose” character be re-used even under the circumstances of “enlargement”? Can the metaphor of the villa still exist in modern times?

The villa can be characterized by compactness (the absence of long corridors), by different types of “rooms” and by its relation with the surrounding landscape. This compactness leads within the urban constrains to the “deepest” office building of Holland.

A “precision-bombardment” of snake-like holes makes it possible to combine light and air with views to the surrounding. The result is an office-landscape where the difference between outside and inside is vague.

The existing nature will be replaced by an elevated heatherroof, under which like a geological formation a series of floors is made. These floors are interconnected by different spatial means: ramps, monumental stairs, mini-hills, grand stairs, slopes, thus forming a route from the surroundings towards the roof.

It causes a continuous interior where the differences in height combine the specific with the general, stimulating the communication patterns. These floors can be “urbanized” the changing demands of the company: a range of office typologies as the salon-, attic-, corridor-, patio- and terrace offices form a retrospective of the existing villas.

These floors are supported by a “forrest” of columns and minimal bracing in order to keep the planes as open as possible. The technique is totally hidden in hollow ancient Roman-like floors so that it doesn’t distract the worker from its tasks. The spartanesque concrete terraced floors comment the smoothened and slave-like aspects of comfort.

In materialization the villa echoes the present villas: no false lowered ceiling-systems but a “real” stone ceiling, no clicking wall-systems but “real” walls with sliding doors, no computerfloors but a stone one that does not sound hollow, covered by individually chosen Persian rugs instead of this standard “project-tapestry”, no windows but fullheight glass sliding-doors opening towards balconies.

The facade has become the result of a “datascape” of demands. In order to keep the view towards the surrounding nature as open as possible, it tries even to become a facade by proposing a system of megastore heaters. Since this wasn’t legally allowed, it will be replaced by 35 species of glass, caused of the differences in height and position. The spatial richness of the interior will thus be reflected by this “rose-window” of glasstypes.

VILLA VPRO

Reinterpreting the typology of the villa, MVRDV’s offices for a broadcasting company form a rich internal landscape characterized by placemaking, incident and spatial delight.

VPRO is an independent broadcasting organization which grew up piecemeal in villas scattered across Hilversum. When it decided to bring its operations together on a campus shared with other co-operating television companies, the outfit was determined to retain the informality and particularness of the original working surroundings. Programmes, it was thought, owed their character partly to the great variety of spaces in which they had been conceived: drawing rooms, sun porches, attics and so on. So the brief of the new building called for an evocation (but not reproduction) of that atmosphere, and for the easy and informal connections between interior and exterior realms offered by domestic buildings. The new building was to be a big villa.

None of this was easy to achieve, for the plan was forced by zoning and height restrictions to be very compact, and the resulting square has been called the deepest office plan in the Netherlands. In fact, the VPRO headquarters is about as similar to the villas that edge its site as the medieval villa was to the Roman villa from which it descended. VPRO is very much bigger than the existing buildings, and its rigorous Euclidean outline necessitates different relationships between interior and exterior than can be obtained in the informal additive plans of nineteenth- and twentieth- century villas. So informality and intimate connections between inside and out have been created by carving into the mass with voids, allowing levels and spaces to flow into each other and, in places, stepping and warping the otherwise rigorous orthogonal gridded structure.

The main warp is at the entrance in the north-east corner, where the first floor buckles upwards and backwards in a two-directional curve to make a porch. You might think from the basic description of the geometry that arrival would be celebrated. It is not. The porch is in fact part of the rather dismal car park that flows in from the big external one to occupy much of the plan at this level. It is rather like a factory that has gone a bit wonky at the corner, and the entrance, a glass box that descends among parked vehicles from the curved slab above, is neither welcoming nor even immediately obvious. It’s just that there can be nowhere else to go.

Once inside the box, you have choice of Dutchly steep stairs or lift. So when you arrive at the first floor entrance hall, the generosity, luminance and playfulness of the surroundings are an immediate delight. The double-height space round the stair head is surrounded by a gallery from which light pours down. Up towards it rises the polished concrete floor like a gently rolling hillside (this is of course the positive side of the double concave curve that forms the porch outside). Ahead is a strange vista in which the wall curves backwards, being penetrated by a slot that offers a vista of complex spaces beyond. Above is a chandelier; under your feet a fine large Oriental rug laid simply on the polished concrete. Everywhere, there are sensual invitations to explore, to penetrate deeper into the building. Unexpected shafts of light, changes of level and height make a densely interwoven tapestry of places, through and past which are paths – the most obvious is the long stepped volume of the cafeteria that rises gently southwards from the second floor up through higher levels.

The spatial sequences can be regarded as promenades architecturales, braided double helix-like, which gradually spiral up to the roof. Here, the grass of the site has been lifted up into the air and the hard interior landscapes through which you have been walking become soft and green again. The turf roof is mined by shafts and slits which bring light down into the middle of the deep plan. In a sense, these voids are the negatives of the plans of the neighbouring villas, so in the new building, as in the old ones, there are few spaces that do not have access (through sliding glass walls) to a garden, court, terrace or balcony. Originally, the architects wanted to make a building without a material exterior by using hot air curtains like the ones that guard the entrances to department stores. Not surprisingly, the proposal was turned down by the building authorities, and external walls now have no less than 35 different kinds of glass, carefully chosen according to orientation and aspect, internal use and character.

They add to the great variety of spaces offered by the building. Rarely has that strange recurrent dream that all architects have, of exploring a forgotten and seemingly endless complex full of surprise and mystery, been so clearly translated into reality in a modern building (real examples from the past range from Hadrian’s Villa to the Soane Museum). Places vary in nature from library and study, to workshop and factory, to club and refectory ( the most functionally determined rooms: archives, studios and so on, are in the basement which only spasmodically takes part in the volumetric flow). Spatial variety ranges from cell to gulch, hill to promenade, flying stair to cave. Materials are apparently simple, sometimes almost crude: concrete, wood, post and mesh balustrades, translucent plastic round vertical ducts and in the ceiling of the cafeteria. They are hard, so spaces are rather noisy and sometimes acoustically institutional, with the little absorption provided by sisal mats and exposed timber. And in an outfit so devoted to particular place, it seems curious that individuals are prevented by management policy from displaying private possessions and plants.

In this, the building is very different from its obvious ancestor, Herman Hertzberger’s Centraal Beheer which, at least in its original incarnation, was jungle-like with the users’ creepers and shrubs, and full of the sound of singing birds. As Peter Buchanan has pointed out, while the Hertzberger building is tightly organized, VPRO is loose and labyrinthine. Yet the very rigorousness and repetition of spatial structure at Centraal Beheer (as at least as first managed) offered individuals and small groups a great deal of potential for identifying with particular place (hence the birds and plants). Both in management style and spatial organization, VPRO is much less amenable to individual appropriation of territory. It is a post-modern building in which, while you probably have no very clear place of your own, you are offered so many different kinds of experience that you can make up a different story for yourself every day, in which you can move from workshop to study, canteen to lecture theatre as your own plot demands. It’s a rich enough mix to give hot desking a human face.

There are some dud moments: crudity of detailing, sub-surrealism like the chandelier, and the dreary car park entrance. (Though perhaps that is a contemporary echo – shared with Centraal Beheer – of the Dutch tradition, which goes back to the seventeenth century, of impassive exteriors masking wonderful spatial delights within). And there is a strong whiff of OMA about VPRO (no Dutch architects of the partnership’s generation can avoid the presence in one way or other). But, here at least, MVRDV do not share Koolhaas’s heartless anti-humanism. Much more than that, at VPRO, the young firm has generated a building which, like Centraal Beheer, will influence ways in which we will all think when trying to make decent workplaces.

Specific Vocabulary (Journal)

VILLA VPRO

For the VPRO, the dutch “artistic” broadcasting company, a new building means leaving the present condition of more or less 11 villas. Villas, which played throughout the years a vital role in the identity of the VPRO. People, who used to work in rooms-en-suite, attics, serres and bel-etages will have to find their spot in a new and “real” office-environment.

Should this existing identity be stopped? Can the present improvised use of space, which often had an influence on the programs that were produced, be combined with the required “efficiency” of modern office? And can this “loose” character be re-used even under the circumstances of “enlargement”? Can the metaphor of the villa still exist in modern times?

The villa can be characterized by compactness (the absence of long corridors), by different types of “rooms” and by its relation with the surrounding landscape. This compactness leads within the urban constrains to the “deepest” office building of Holland.

A “precision-bombardment” of snake-like holes makes it possible to combine light and air with views to the surrounding. The result is an office-landscape where the difference between outside and inside is vague.

The existing nature will be replaced by an elevated heatherroof, under which like a geological formation a series of floors is made. These floors are interconnected by different spatial means: ramps, monumental stairs, mini-hills, grand stairs, slopes, thus forming a route from the surroundings towards the roof.

It causes a continuous interior where the differences in height combine the specific with the general, stimulating the communication patterns. These floors can be “urbanized” the changing demands of the company: a range of office typologies as the salon-, attic-, corridor-, patio- and terrace offices form a retrospective of the existing villas.

These floors are supported by a “forrest” of columns and minimal bracing in order to keep the planes as open as possible. The technique is totally hidden in hollow ancient Roman-like floors so that it doesn’t distract the worker from its tasks. The spartanesque concrete terraced floors comment the smoothened and slave-like aspects of comfort.

In materialization the villa echoes the present villas: no false lowered ceiling-systems but a “real” stone ceiling, no clicking wall-systems but “real” walls with sliding doors, no computerfloors but a stone one that does not sound hollow, covered by individually chosen Persian rugs instead of this standard “project-tapestry”, no windows but fullheight glass sliding-doors opening towards balconies.

The facade has become the result of a “datascape” of demands. In order to keep the view towards the surrounding nature as open as possible, it tries even to become a facade by proposing a system of megastore heaters. Since this wasn’t legally allowed, it will be replaced by 35 species of glass, caused of the differences in height and position. The spatial richness of the interior will thus be reflected by this “rose-window” of glasstypes.

VILLA VPRO

Reinterpreting the typology of the villa, MVRDV’s offices for a broadcasting company form a rich internal landscape characterized by placemaking, incident and spatial delight.

VPRO is an independent broadcasting organization which grew up piecemeal in villas scattered across Hilversum. When it decided to bring its operations together on a campus shared with other co-operating television companies, the outfit was determined to retain the informality and particularness of the original working surroundings. Programmes, it was thought, owed their character partly to the great variety of spaces in which they had been conceived: drawing rooms, sun porches, attics and so on. So the brief of the new building called for an evocation (but not reproduction) of that atmosphere, and for the easy and informal connections between interior and exterior realms offered by domestic buildings. The new building was to be a big villa.

None of this was easy to achieve, for the plan was forced by zoning and height restrictions to be very compact, and the resulting square has been called the deepest office plan in the Netherlands. In fact, the VPRO headquarters is about as similar to the villas that edge its site as the medieval villa was to the Roman villa from which it descended. VPRO is very much bigger than the existing buildings, and its rigorous Euclidean outline necessitates different relationships between interior and exterior than can be obtained in the informal additive plans of nineteenth- and twentieth- century villas. So informality and intimate connections between inside and out have been created by carving into the mass with voids, allowing levels and spaces to flow into each other and, in places, stepping and warping the otherwise rigorous orthogonal gridded structure.

The main warp is at the entrance in the north-east corner, where the first floor buckles upwards and backwards in a two-directional curve to make a porch. You might think from the basic description of the geometry that arrival would be celebrated. It is not. The porch is in fact part of the rather dismal car park that flows in from the big external one to occupy much of the plan at this level. It is rather like a factory that has gone a bit wonky at the corner, and the entrance, a glass box that descends among parked vehicles from the curved slab above, is neither welcoming nor even immediately obvious. It’s just that there can be nowhere else to go.

Once inside the box, you have choice of Dutchly steep stairs or lift. So when you arrive at the first floor entrance hall, the generosity, luminance and playfulness of the surroundings are an immediate delight. The double-height space round the stair head is surrounded by a gallery from which light pours down. Up towards it rises the polished concrete floor like a gently rolling hillside (this is of course the positive side of the double concave curve that forms the porch outside). Ahead is a strange vista in which the wall curves backwards, being penetrated by a slot that offers a vista of complex spaces beyond. Above is a chandelier; under your feet a fine large Oriental rug laid simply on the polished concrete. Everywhere, there are sensual invitations to explore, to penetrate deeper into the building. Unexpected shafts of light, changes of level and height make a densely interwoven tapestry of places, through and past which are paths – the most obvious is the long stepped volume of the cafeteria that rises gently southwards from the second floor up through higher levels.

The spatial sequences can be regarded as promenades architecturales, braided double helix-like, which gradually spiral up to the roof. Here, the grass of the site has been lifted up into the air and the hard interior landscapes through which you have been walking become soft and green again. The turf roof is mined by shafts and slits which bring light down into the middle of the deep plan. In a sense, these voids are the negatives of the plans of the neighbouring villas, so in the new building, as in the old ones, there are few spaces that do not have access (through sliding glass walls) to a garden, court, terrace or balcony. Originally, the architects wanted to make a building without a material exterior by using hot air curtains like the ones that guard the entrances to department stores. Not surprisingly, the proposal was turned down by the building authorities, and external walls now have no less than 35 different kinds of glass, carefully chosen according to orientation and aspect, internal use and character.

They add to the great variety of spaces offered by the building. Rarely has that strange recurrent dream that all architects have, of exploring a forgotten and seemingly endless complex full of surprise and mystery, been so clearly translated into reality in a modern building (real examples from the past range from Hadrian’s Villa to the Soane Museum). Places vary in nature from library and study, to workshop and factory, to club and refectory ( the most functionally determined rooms: archives, studios and so on, are in the basement which only spasmodically takes part in the volumetric flow). Spatial variety ranges from cell to gulch, hill to promenade, flying stair to cave. Materials are apparently simple, sometimes almost crude: concrete, wood, post and mesh balustrades, translucent plastic round vertical ducts and in the ceiling of the cafeteria. They are hard, so spaces are rather noisy and sometimes acoustically institutional, with the little absorption provided by sisal mats and exposed timber. And in an outfit so devoted to particular place, it seems curious that individuals are prevented by management policy from displaying private possessions and plants.

In this, the building is very different from its obvious ancestor, Herman Hertzberger’s Centraal Beheer which, at least in its original incarnation, was jungle-like with the users’ creepers and shrubs, and full of the sound of singing birds. As Peter Buchanan has pointed out, while the Hertzberger building is tightly organized, VPRO is loose and labyrinthine. Yet the very rigorousness and repetition of spatial structure at Centraal Beheer (as at least as first managed) offered individuals and small groups a great deal of potential for identifying with particular place (hence the birds and plants). Both in management style and spatial organization, VPRO is much less amenable to individual appropriation of territory. It is a post-modern building in which, while you probably have no very clear place of your own, you are offered so many different kinds of experience that you can make up a different story for yourself every day, in which you can move from workshop to study, canteen to lecture theatre as your own plot demands. It’s a rich enough mix to give hot desking a human face.

There are some dud moments: crudity of detailing, sub-surrealism like the chandelier, and the dreary car park entrance. (Though perhaps that is a contemporary echo – shared with Centraal Beheer – of the Dutch tradition, which goes back to the seventeenth century, of impassive exteriors masking wonderful spatial delights within). And there is a strong whiff of OMA about VPRO (no Dutch architects of the partnership’s generation can avoid the presence in one way or other). But, here at least, MVRDV do not share Koolhaas’s heartless anti-humanism. Much more than that, at VPRO, the young firm has generated a building which, like Centraal Beheer, will influence ways in which we will all think when trying to make decent workplaces.

Web (grammar)

rooms-en-suite, serres,bel-etages : palabras tomadas del francés

find their spot: expresión para “encontrar su lugar”

re-used: formación de palabras con –

snake-like: -like para decir “con forma de”

heatherroof: ¿por qué juntar “heather roof”?

forrest: en vez de “forest”

in order to: en lugar de “for”

Journal (grammar)

placemaking: unión de sustantivo y verbo, “place” y “make”, para hacer una única palabra

scattered across: “across” y no algo como “over” u “on”

and so on: para decir “etcétera”

for the plan was forced: “for” con el significado de “y es que”

created by: “by” para decir “por medio de”

it is not: pues no es así

flows in: “in” para indicar penetración

pours down: “down” para indicar que la luz viene de arriba hacia abajo

laid simply on: “on” y no “over”

spiral up: un verbo que parece un nombre y “up” para indicar ascensión

into the air: penetrar en un vacío ¿?

in a sense: es decir, en resumen

turned down: desechado “down” por completo

prevented from: “from” en lugar de “of”

jungle-like: “-like” para significar “en forma de”

as at least as: al menos como

in one way or other: de una forma u otra

VILLA VPRO

For the VPRO, the dutch “artistic” broadcasting company, a new building means leaving the present condition of more or less 11 villas. Villas, which played throughout the years a vital role in the identity of the VPRO. People, who used to work in rooms-en-suite, attics, serres and bel-etages will have to find their spot in a new and “real” office-environment.

Should this existing identity be stopped? Can the present improvised use of space, which often had an influence on the programs that were produced, be combined with the required “efficiency” of modern office? And can this “loose” character be re-used even under the circumstances of “enlargement”? Can the metaphor of the villa still exist in modern times?

The villa can be characterized by compactness (the absence of long corridors), by different types of “rooms” and by its relation with the surrounding landscape. This compactness leads within the urban constrains to the “deepest” office building of Holland.

A “precision-bombardment” of snake-like holes makes it possible to combine light and air with views to the surrounding. The result is an office-landscape where the difference between outside and inside is vague.

The existing nature will be replaced by an elevated heatherroof, under which like a geological formation a series of floors is made. These floors are interconnected by different spatial means: ramps, monumental stairs, mini-hills, grand stairs, slopes, thus forming a route from the surroundings towards the roof.

It causes a continuous interior where the differences in height combine the specific with the general, stimulating the communication patterns. These floors can be “urbanized” the changing demands of the company: a range of office typologies as the salon-, attic-, corridor-, patio- and terrace offices form a retrospective of the existing villas.

These floors are supported by a “forrest” of columns and minimal bracing in order to keep the planes as open as possible. The technique is totally hidden in hollow ancient Roman-like floors so that it doesn’t distract the worker from its tasks. The spartanesque concrete terraced floors comment the smoothened and slave-like aspects of comfort.

In materialization the villa echoes the present villas: no false lowered ceiling-systems but a “real” stone ceiling, no clicking wall-systems but “real” walls with sliding doors, no computerfloors but a stone one that does not sound hollow, covered by individually chosen Persian rugs instead of this standard “project-tapestry”, no windows but fullheight glass sliding-doors opening towards balconies.

The facade has become the result of a “datascape” of demands. In order to keep the view towards the surrounding nature as open as possible, it tries even to become a facade by proposing a system of megastore heaters. Since this wasn’t legally allowed, it will be replaced by 35 species of glass, caused of the differences in height and position. The spatial richness of the interior will thus be reflected by this “rose-window” of glasstypes.

VILLA VPRO

Reinterpreting the typology of the villa, MVRDV’s offices for a broadcasting company form a rich internal landscape characterized by placemaking, incident and spatial delight.

VPRO is an independent broadcasting organization which grew up piecemeal in villas scattered across Hilversum. When it decided to bring its operations together on a campus shared with other co-operating television companies, the outfit was determined to retain the informality and particularness of the original working surroundings. Programmes, it was thought, owed their character partly to the great variety of spaces in which they had been conceived: drawing rooms, sun porches, attics and so on. So the brief of the new building called for an evocation (but not reproduction) of that atmosphere, and for the easy and informal connections between interior and exterior realms offered by domestic buildings. The new building was to be a big villa.

None of this was easy to achieve, for the plan was forced by zoning and height restrictions to be very compact, and the resulting square has been called the deepest office plan in the Netherlands. In fact, the VPRO headquarters is about as similar to the villas that edge its site as the medieval villa was to the Roman villa from which it descended. VPRO is very much bigger than the existing buildings, and its rigorous Euclidean outline necessitates different relationships between interior and exterior than can be obtained in the informal additive plans of nineteenth- and twentieth- century villas. So informality and intimate connections between inside and out have been created by carving into the mass with voids, allowing levels and spaces to flow into each other and, in places, stepping and warping the otherwise rigorous orthogonal gridded structure.

The main warp is at the entrance in the north-east corner, where the first floor buckles upwards and backwards in a two-directional curve to make a porch. You might think from the basic description of the geometry that arrival would be celebrated. It is not. The porch is in fact part of the rather dismal car park that flows in from the big external one to occupy much of the plan at this level. It is rather like a factory that has gone a bit wonky at the corner, and the entrance, a glass box that descends among parked vehicles from the curved slab above, is neither welcoming nor even immediately obvious. It’s just that there can be nowhere else to go.

Once inside the box, you have choice of Dutchly steep stairs or lift. So when you arrive at the first floor entrance hall, the generosity, luminance and playfulness of the surroundings are an immediate delight. The double-height space round the stair head is surrounded by a gallery from which light pours down. Up towards it rises the polished concrete floor like a gently rolling hillside (this is of course the positive side of the double concave curve that forms the porch outside). Ahead is a strange vista in which the wall curves backwards, being penetrated by a slot that offers a vista of complex spaces beyond. Above is a chandelier; under your feet a fine large Oriental rug laid simply on the polished concrete. Everywhere, there are sensual invitations to explore, to penetrate deeper into the building. Unexpected shafts of light, changes of level and height make a densely interwoven tapestry of places, through and past which are paths – the most obvious is the long stepped volume of the cafeteria that rises gently southwards from the second floor up through higher levels.

The spatial sequences can be regarded as promenades architecturales, braided double helix-like, which gradually spiral up to the roof. Here, the grass of the site has been lifted up into the air and the hard interior landscapes through which you have been walking become soft and green again. The turf roof is mined by shafts and slits which bring light down into the middle of the deep plan. In a sense, these voids are the negatives of the plans of the neighbouring villas, so in the new building, as in the old ones, there are few spaces that do not have access (through sliding glass walls) to a garden, court, terrace or balcony. Originally, the architects wanted to make a building without a material exterior by using hot air curtains like the ones that guard the entrances to department stores. Not surprisingly, the proposal was turned down by the building authorities, and external walls now have no less than 35 different kinds of glass, carefully chosen according to orientation and aspect, internal use and character.

They add to the great variety of spaces offered by the building. Rarely has that strange recurrent dream that all architects have, of exploring a forgotten and seemingly endless complex full of surprise and mystery, been so clearly translated into reality in a modern building (real examples from the past range from Hadrian’s Villa to the Soane Museum). Places vary in nature from library and study, to workshop and factory, to club and refectory ( the most functionally determined rooms: archives, studios and so on, are in the basement which only spasmodically takes part in the volumetric flow). Spatial variety ranges from cell to gulch, hill to promenade, flying stair to cave. Materials are apparently simple, sometimes almost crude: concrete, wood, post and mesh balustrades, translucent plastic round vertical ducts and in the ceiling of the cafeteria. They are hard, so spaces are rather noisy and sometimes acoustically institutional, with the little absorption provided by sisal mats and exposed timber. And in an outfit so devoted to particular place, it seems curious that individuals are prevented by management policy from displaying private possessions and plants.

In this, the building is very different from its obvious ancestor, Herman Hertzberger’s Centraal Beheer which, at least in its original incarnation, was jungle-like with the users’ creepers and shrubs, and full of the sound of singing birds. As Peter Buchanan has pointed out, while the Hertzberger building is tightly organized, VPRO is loose and labyrinthine. Yet the very rigorousness and repetition of spatial structure at Centraal Beheer (as at least as first managed) offered individuals and small groups a great deal of potential for identifying with particular place (hence the birds and plants). Both in management style and spatial organization, VPRO is much less amenable to individual appropriation of territory. It is a post-modern building in which, while you probably have no very clear place of your own, you are offered so many different kinds of experience that you can make up a different story for yourself every day, in which you can move from workshop to study, canteen to lecture theatre as your own plot demands. It’s a rich enough mix to give hot desking a human face.

There are some dud moments: crudity of detailing, sub-surrealism like the chandelier, and the dreary car park entrance. (Though perhaps that is a contemporary echo – shared with Centraal Beheer – of the Dutch tradition, which goes back to the seventeenth century, of impassive exteriors masking wonderful spatial delights within). And there is a strong whiff of OMA about VPRO (no Dutch architects of the partnership’s generation can avoid the presence in one way or other). But, here at least, MVRDV do not share Koolhaas’s heartless anti-humanism. Much more than that, at VPRO, the young firm has generated a building which, like Centraal Beheer, will influence ways in which we will all think when trying to make decent workplaces.

[1] Datos recogidos por la U. P. M. “Estudio sobre el empleo de los graduados de la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid” 2000.

[2] GESE. Es el Gabinete Educativo de Servicio al Estudiante de la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid.

[3] Entre los profesores de Inglés E.S.P. se refiere a English for Specific Purposes o lo que es igual Inglés para Fines Específicos en castellano.

[4] Adaptación del término inglés kinesthetic. No aparece en el Diccionario de la Real Academia Española.Los traductores de la edición en español de Richards y Lockhart optan por Cinestético y García Santa Cecilia lo traduce como Cinestésico.

[5] Por motivos de espacio se presenta un solo trabajo. El ejemplo que se presentan en el apéndice 2 ha sido cedido por cortesía de la alumna Lydia Mª Inglis Redondo, alumna de la asignatura Aplicaciones Profesionales en Inglés para Arquitectos del curso 2001/2002, semestre de primavera.

|